An AFF Instructor experienced an entanglement after a routine freefall when her first-jump student threw his main pilot chute and the bridle became entangled with her camera helmet. While she worked to clear the bridle from her helmet, the student’s main pin extracted and the container flaps opened. The reserve-side instructor noticed this and placed his hand on the main bag, holding it in the container while the main-side instructor tried to clear the bridle. After several seconds, she released her helmet, throwing it (and the student’s pilot chute) into the air, consequently deploying the student’s main parachute. Thanks to both instructors remaining calm and making correct decisions, the jump ended positively for everyone. The entire incident lasted only a few seconds.

Most fatal (and non-fatal) skydiving accidents fall into just a handful of categories, the most common being low turns, low parachute deployments, incorrect emergency procedures and equipment problems. Every now and then, an incident occurs that is outside of the ordinary, and these have just as much to teach us as more common ones. Following are some of the more unusual fatal incidents that have occurred since 1999 that serve as valuable lessons for everyone skydiving today.

Entanglements

These fatal accidents are just a few examples of unusual situations involving entanglements that occurred over the past 22 years:

- A jumper with 800 jumps made a front-riser turn at approximately 300 feet. His steering line caught on the GoPro camera mounted on the front of his helmet. When he let up on the front riser to stop the turn, the parachute continued to spin due to the trapped steering line, and he died from the hard impact with the ground.

This accident shows how additional equipment such as a helmet-mounted GoPro camera can create dangerous situations. Jumpers should consider all the risks when adding equipment, have a plan to minimize those risks and rehearse the scenarios for handling problems if they occur.

- A jumper with 6,000 jumps videoed a 6-way formation skydive. He deployed his main parachute, which malfunctioned. He then released his main parachute and pulled his reserve ripcord while he was in a back-to-earth position. The reserve bridle snagged on the back of his camera helmet and stopped the reserve from deploying. He struck the ground without a deployed parachute.

This jumper did not use a reserve static line, presumably in the mistaken belief that they add risk when using a helmet-mounted video camera. However, the use of an RSL or main-assisted-reserve-deployment (MARD) device would have likely prevented this fatality.

Removing the twists from each brake line while repacking the main parachute is a good habit to get into.

- A jumper with 600 jumps was observed under his main parachute spiraling three separate times below 1,000 feet. The final turn started at a low altitude and continued to impact. He was observed with both his hands fully up while the main canopy was spinning. An inspection revealed a tension knot on one brake line that was two feet above the toggle. The tension knot was catching on the guide ring of the main riser, which held the parachute in a turn.

Removing the twists from each brake line while repacking the main parachute is a good habit to get into. Brake lines can twist themselves enough to create tension knots such as this one. Had this jumper discovered the problem above his decision altitude, it would have allowed for a cutaway and reserve parachute deployment. As a last resort, if a brake line is trapped on one side, pulling down the opposite toggle can counter the turn and keep the parachute flying straight and level. Landing in straight-and-level flight without a landing flare is not an optimum situation, but it is better than landing a parachute in a spinning descent.

- A tandem pair experienced a main parachute malfunction on a system on which the instructor had disconnected the reserve static line. The instructor pulled the cutaway handle and released the main parachute, then pulled the reserve ripcord after a short delay as the pair began to flip forward. The reserve pilot chute and bridle entangled with the tandem instructor’s foot, creating a horseshoe malfunction. The reserve lines eventually unstowed, and the freebag released from the reserve parachute, allowing the reserve to begin inflation. However, due to severe line twists caused by the entanglement, the reserve parachute was unable to fully inflate before the pair struck the ground at a high rate of descent. Both the student and the instructor died from the hard impact.

The use of an RSL would almost certainly have released the reserve parachute quickly enough to have prevented this fatal accident.

Experiencing an entanglement of any kind is never a good thing. The above incidents teach us the importance of carefully maintaining and packing equipment, rehearsing and properly performing emergency procedures and using an RSL or MARD as a backup device.

Aircraft-Related Incidents

Over the years there have been a several fatal accidents involving the jump aircraft. While pilot actions certainly come into play in these circumstances, there are also usually ways for the jumpers to change the outcome.

- A student on his 25th jump, an A-license check dive, was in the door of a King Air facing outward as his instructor was outside facing inward for a non-gripped exit. The student noticed that the instructor’s reserve ripcord handle had dislodged from the harness, so he grabbed it and the instructor’s jumpsuit, possibly attempting to reseat the handle or keep the instructor from leaving the airplane. The instructor let go of the airplane while the student held onto the reserve handle, and the reserve deployed over the tail of the airplane, pulling the instructor into the leading edge and over the tail. He died instantly and descended into a wooded area under the reserve parachute.

Floating reserve handles are not uncommon and can be prevented with a careful gear check before exit. The loose handle itself doesn’t present much danger, because it does not have enough weight to extract the pin, but if it snags on something or is pulled, the reserve will launch. Unfortunately, the student grabbed the instructor’s handle at the worst possible second, and the instructor did not look down before exit and notice.

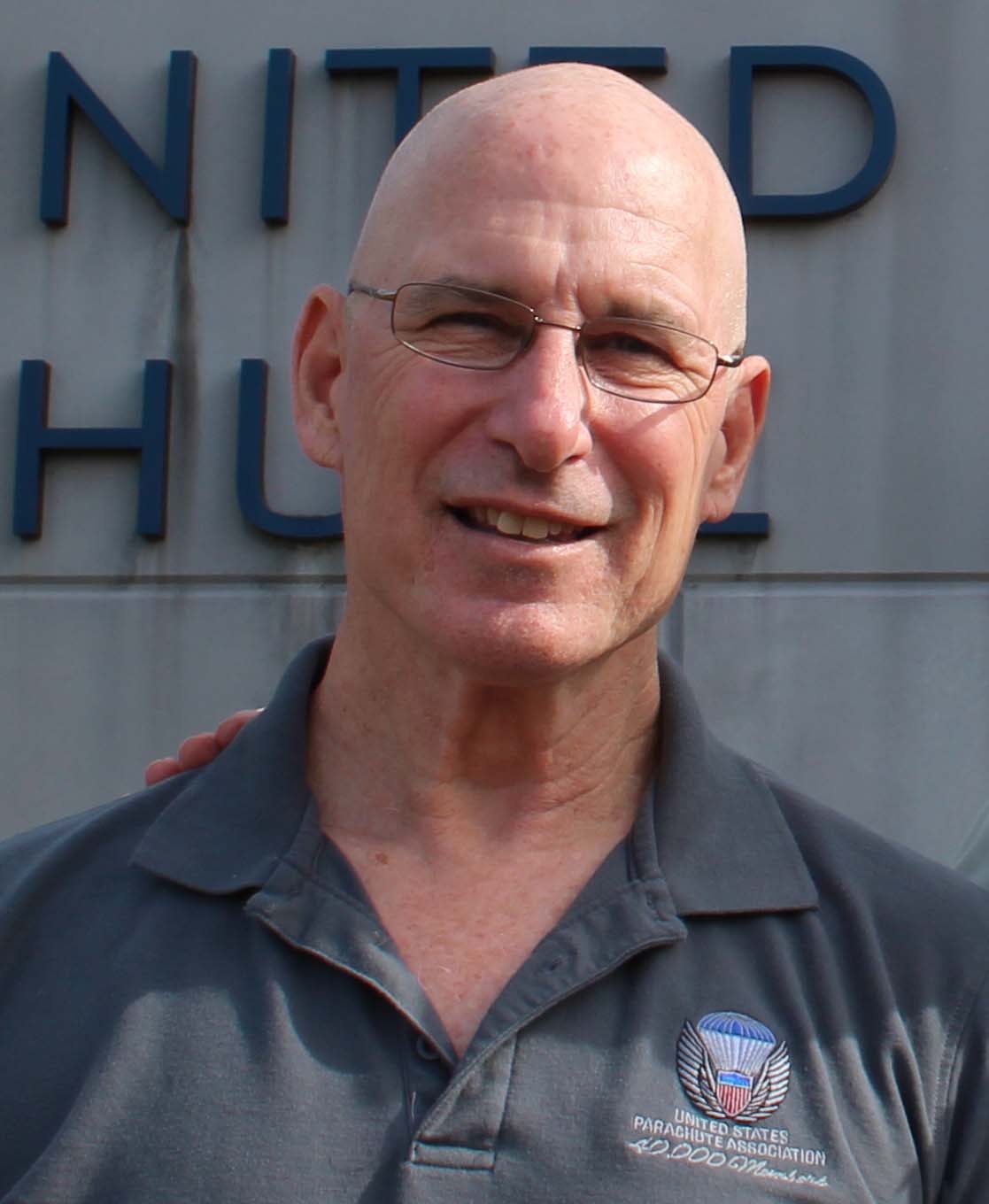

While pilot actions certainly come into play … there are also usually ways for the jumpers to change the outcome. Photo by Gary Fletcher.

- A Twin Otter and a King Air were flying in formation with the King Air in the trail position for a formation skydive with approximately 32 skydivers. As the jumpers were climbing out during jump run, the King Air overtook the Twin Otter and ended up in front. As the last divers exited the King Air, one of the jumpers struck the right propeller of the Twin Otter and was killed by the impact. Another jumper was able to catch her in freefall and deploy her reserve, but the reserve was badly damaged and did not fully inflate.

There were several opportunities to change the outcome of this fatality. As soon as the King Air moved out of its planned position, the pilots could have aborted jump run and told the jumpers to stay put (or climb back in if climb-out had started). The jumpers also could have asked for the jump run to be aborted or for a go-around. Although it is difficult for a late diver to notice the situation that caused this fatality, the jumper may have been able to avoid the propeller if she had seen the position of the Twin Otter as she exited. (She was initially looking back toward the King Air and then turned to dive toward the formation.) This fatality, which occurred in the early 2000s and has never been repeated, is a good example of how a chain of events, not just a single problem, can lead to a tragedy. Breaking just one link of the chain can stop a fatality from occurring.

- A jumper climbed out of a Cessna 206 onto the step above the landing gear, and his main deployment bag dropped out of his container in front of the landing gear. The suspension lines unstowed, and the main parachute inflated and wrapped around the horizontal stabilizer of the airplane. The inflated main parachute pulled the jumper in front of the landing gear and then left him trailing behind the tail. The pilot and other jumpers successfully exited the airplane and landed safely. The airplane descended in an inverted spin until impact with the ground.

This accident shows the importance of keeping the main container closed as tightly as possible with a closing loop of the correct length. A gear check before exit—which should include checking your leg straps, chest strap and handles and having someone else check your main and reserve pin—will help ensure your equipment is ready for the skydive.

Off-Field Landings

Landing safely is a top priority for every skydive, and landing in a familiar area is safer than landing off-field. Following a series of fatal accidents related to off-field landings in the early 2000s, USPA updated Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 5-1 to include off-field landing recommendations.

- A jumper with 450 jumps deployed his main parachute too far away from the drop zone to land there. He passed over several large open fields while flying toward the drop zone, opting to head to a close field. He misjudged his final descent path as he descended, hitting the tops of trees surrounding the field he chose. His parachute collapsed, and he landed hard at the edge of the field.

Once it is obvious that the regular drop zone landing area is not an option, landing in a large, open area free of any obstacles should be the priority, not continuing your descent over hazardous areas to land closer to the drop zone.

Trying to beat weather to squeeze in a jump is never a good idea, especially when it involves violent thunderstorms and strong winds. Photo by Javier Ortiz.

- A jumper with approximately 400 jumps deployed her main parachute at 3,000 feet and was observed backing up away from the drop zone due to strong winds. She landed just downwind from a row of trees in a field filled with tree stumps. Ground winds were reported to be 20 knots gusting to 30 knots. The jumper landed hard, and her canopy dragged her backward into a stump. She died instantly from a broken neck.

Jumping in strong winds greatly increases the chances of being injured or killed from a landing accident.

- A tandem pair exited from a Cessna 182 at 8,000 feet just ahead of a strong group of thunderstorms that had created a fast-moving squall line. After the main parachute deployed, the strong winds pushed the pair backward, carrying them approximately 100 yards over a large lake. After landing in the water, the instructor disconnected the student from his harness, and the student was able to swim to shore. The instructor climbed out of the harness-and-container system but drowned before he was able to reach the shoreline.

Trying to beat weather to squeeze in a jump is never a good idea, especially when it involves violent thunderstorms and strong winds. In this circumstance, there was also a large body of water that could not be avoided, which added to the danger.

Sticking to the basics is a good way to reduce any type of skydiving risk. It is impossible to predict all the unusual situations that can lead to a skydiving injury or fatality, but the precautions you can take are almost always the same. Reduce the chances of experiencing an unusual injury or fatality the same way you do a common one: Rehearse emergency procedures frequently, carefully plan and execute each skydive and properly maintain and check your equipment. It’s the common things that will keep you safe in uncommon circumstances.

About the Author

About the Author

Jim Crouch, D-16979, is an FAA-rated Airline Transport Pilot based in Tampa, Florida. From 2000 to 2018, he was the director of safety and training at USPA.