On September 10, 1995, 10 skydivers, a pilot and one person on the ground died when a jump plane crashed shortly after takeoff from the West Point Airport (now called the Middle Peninsula Regional Airport) in West Point, Virginia. Twenty-five years later, it is still a significant memory for those who lost loved ones on that tragic sunset load.

About a month before the crash, I was talking to Dave Ropp, who co-owned Skydive Westpoint Inc. with Ruth Sondheimer, when I heard the Beechcraft Queen Air taxi past, heading toward Runway 27 with a load of jumpers. As the plane roared down the runway picking up speed, I said, “Something is not right with that airplane. To me it sounds like a small-block Chevy with a bent push rod.” I was an auto mechanic at the time, so I was very familiar with normal and abnormal engine sounds. The exhaust note emanating from that airplane always sounded different to me, with an underlying popping noise that was hard to explain. Ropp looked at me and said, “Yeah, one day we might be pulling that plane out of the river.” (The York River wrapped around the airport on its west and south ends.)

A few weeks later, Ropp and 11 others died in the fiery crash after the airplane took off on runway 9, lost power on the right engine at approximately 300 feet and stalled. It crashed into the back of a house, killing a preacher who was sitting on his back porch reading his Bible. Had that departure been to the west, the plane may have crashed into the river as Ropp had predicted. It has haunted me for much of the past 25 years.

The Queen Air

The Queen Air was relatively new to the drop zone. The Peninsula Skydivers skydiving club had been jumping from a different Queen Air, which experienced a landing-gear failure five months earlier. The club jumped from a Cessna 182 for a few months while the plane owners decided whether to fix the landing gear or find another airplane. They finally purchased another Queen Air somewhere around July of that year instead of fixing the old one. The new Queen Air was flying as a jump plane before it arrived at West Point. According to the National Transportation Safety Board report following the accident, it had been modified for jumping in 1990.

From the moment that Queen Air arrived at West Point, the right engine was finicky. The jumpers would board the plane and after taxiing to the hold-short line of the runway, the pilot would perform a run-up on each engine. (This is a normal procedure for piston-powered aircraft.) Frequently, the right engine would pop and backfire during the run-up, and the pilot would taxi back and unload the jumpers, work on the right engine for a while and start the whole process over again. Then, if the engines ran smoothly during that run-up, the pilot would take off. The jumpers would look at each other nervously, then shrug without saying a word. It became the new normal routine for this airplane. “We just need it to get to 1,000 feet,” was the reasoning of the many jumpers who just assumed they would bail out if the airplane had a problem. Of course, it is now widely known that 1,000 feet doesn’t work as a realistic altitude for 10 jumpers to bail out of a crippled twin-engine airplane that is barely flying. But in 1995, that was the plan.

In the investigation that followed the crash, the NTSB determined that this particular model of Queen Air had not been approved for flight with the door removed. The report stated: “The investigation revealed that this model airplane was not on the eligibility list for flight with the cabin door removed. The Type Certificate Data Sheet for certain Beech 65 series airplanes listed several models as eligible for such door removal, but the Beech Model 65 was not one of those airplanes. A Flight Manual Supplement that appeared to authorize such door removal was provided to investigators by the operator. Examination of this document revealed that it had been altered by an unknown person. There were no records of this model having been flight tested and authorized for such door removal.”

In the investigation that followed the crash, the NTSB determined that this particular model of Queen Air had not been approved for flight with the door removed. The report stated: “The investigation revealed that this model airplane was not on the eligibility list for flight with the cabin door removed. The Type Certificate Data Sheet for certain Beech 65 series airplanes listed several models as eligible for such door removal, but the Beech Model 65 was not one of those airplanes. A Flight Manual Supplement that appeared to authorize such door removal was provided to investigators by the operator. Examination of this document revealed that it had been altered by an unknown person. There were no records of this model having been flight tested and authorized for such door removal.”

Several similar models of Beech 65 airplanes are authorized for flight with the door removed, and although this model was not, it’s not necessarily an indicator that the plane was unsafe to fly with the door removed. It simply had not been through the certification process. However, someone had altered the Flight Manual Supplement to make it look as though the plane was within FAA regulations when it was not.

The NTSB also determined that the plane was 169 pounds over the gross allowed weight and the center of gravity was 2.7 inches aft of where it should have been. The NTSB determined this based on the positions of the bodies after the crash and not necessarily where they started out. The jumpers aboard used seatbelts, but that still allowed for some movement by each jumper both fore and aft.

In the end, the NTSB saddled the majority of the blame on the pilot, which is frequently the case in a plane crash investigation. The NTSB listed the following findings in its report:

- Preflight planning/preparation—inadequate—pilot in command

- Maintenance, modification—improper

- Aircraft weight and balance—exceeded—pilot in command

- Airspeed (VMC)*—not obtained/maintained—pilot in command [*velocity—minimum control]

- Aircraft control—not maintained—pilot in command

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot’s inadequate preflight/preparation, his failure to ensure proper weight and balance of the airplane, and his failure to obtain/maintain minimum control speed, which resulted in a loss of aircraft control after loss of power in one engine. A factor relating to the accident was: loss of power in the right engine for undetermined reason(s).”

The national and local press coverage of the accident was substantial. An airplane crashing into the home of a minister who was reading his Bible while sitting on his back porch made for sensational news coverage. In the two weeks following the crash, families held funerals for all 12 victims, and the West Point airport hosted a separate memorial event that drew more than 500 attendees.

For the jumpers, two solid weeks of attending funerals while planning a large memorial was both depressing and exhausting. On top of that, news coming out of the investigation about the airplane being overweight, out of CG and not approved for flight with the door removed was not only surprising, it also added to the depressing times.

Normalization of Deviance

How could this have happened? How could safety-minded jumpers continue to board an airplane, week after week, when it was exhibiting signs of trouble? The answer is a phenomenon known as normalization of deviance.

How could this have happened? How could safety-minded jumpers continue to board an airplane, week after week, when it was exhibiting signs of trouble? The answer is a phenomenon known as normalization of deviance.

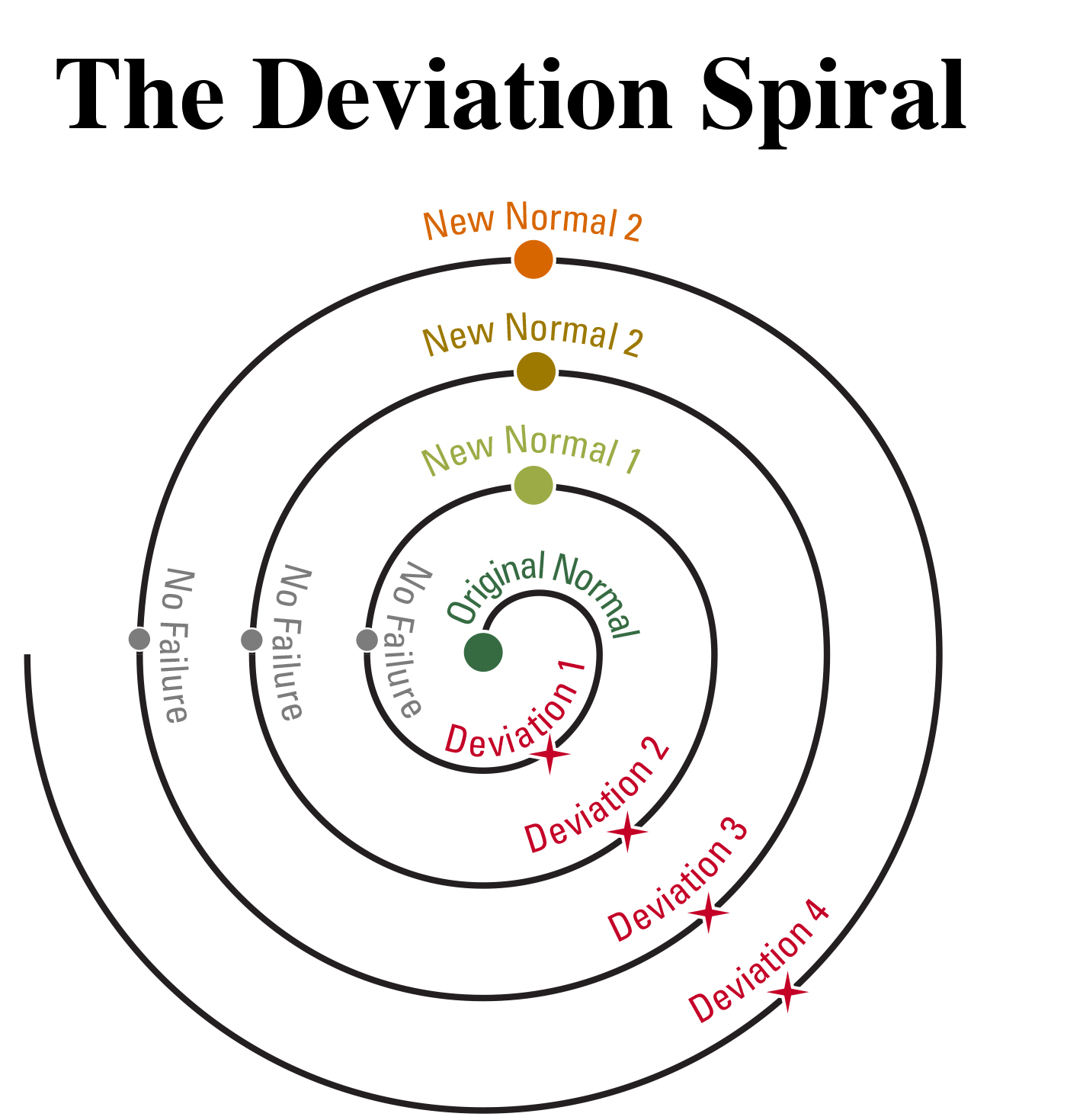

Diane Vaughan is a sociologist who identified and coined the term “normalization of deviance” while investigating the underlying causes of the 1986 NASA Challenger explosion. She found that at NASA, many safety protocols began to relax, which created a new normal that reduced many of the safety parameters set by the NASA engineers. Eventually, enough of the unsafe conditions aligned to cause the explosion and total destruction of the Challenger space shuttle and loss of the crew on January 28, 1986. Vaughan wrote, “Social normalization of deviance means that people within the organization become so much accustomed to a deviation that they don’t consider it as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceed their own rules for the elementary safety.”

Normalization of deviance occurs in almost every facet of daily life, and yet we go on each day, oblivious to the fact that it is occurring. In most cases, the deviation is not life-threatening, as it can be in skydiving and aviation. Something as simple as ignoring the need to change the oil in your vehicle is a form of normalization of deviance. You let it lapse for 1,000 miles past the normally scheduled distance between changes, and nothing bad immediately happens. So, it becomes the new normal to extend the oil-change interval. Suddenly, you are surprised when the engine fails much sooner than it should have if the oil was changed more frequently, as recommended by the manufacturer. Because nothing bad was immediately happening from extending the oil-change interval, the looming failure went undetected.

Normalization of deviance in skydiving can take many forms. One not-uncommon example is continuing to pack and jump a rig that has a closing loop that is too long. When nothing bad immediately happens, the jumper keeps jumping with it that way and accepts the loosely closed container as the new normal. It’s only when another element gets into the mix that a dangerous situation develops. Let’s say the jumper brushes the back of their rig against the edge of the jump door during climbout and—because there is almost no tension on the closing loop—the container opens, and the main parachute deploys into the tail of the airplane. The normalization of deviance—accepting a too-long closing loop because the container stayed closed for a number of jumps—led to a lower level of safety.

In the case of the Queen Air crash, normalization of deviance led to the continued operation of an airplane that was clearly exhibiting signs of trouble on a regular basis. Many of the licensed jumpers at West Point were not happy with the semi-regular popping and backfiring coming out of the right engine. However, while many were uneasy about the reliability of the airplane, everyone continued to jump from it. The plane continued to fly each weekend. When nothing bad happened, the popping of the engine became the new normal. Occasionally, someone would casually discuss it, but nothing changed. The jumpers trusted the judgment of the owners and the pilot, who were also skydivers and close friends.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to see where things could have been different. The pilot (who was also a part owner of the plane) and the other owners of the airplane should have ceased flying jumpers until there was 100-percent confidence that the mechanical issues were resolved. Those like myself, who felt strongly there was an issue with the airplane, should have been more insistent and refused to jump from the airplane until it was reliable.

Normalization of deviance may also have allowed the Queen Air to end up 169 pounds over its weight limit. In 1995, staff put together the manifest—which was basically just a list of names on paper—for each load. It was common practice at the time to use a standard weight for each jumper and the pilot. So, if the manifest staff at West Point used 180 pounds as the standard for each person, it would have taken only four jumpers with an exit weight of 220-225 pounds for the airplane to end up 169 pounds over the gross weight limit. It would be easy to overlook four larger jumpers on a load of 10. Today, almost every drop zone uses manifest software that calculates a weight and balance based on actual exit weights for each jumper. Alarms go off to alert manifest if the load exceeds the maximum weight limit, regardless of how many slots are filled. This is just one of the many improvements that the skydiving industry has made to maintain safety standards.

Constant Vigilance

Maintaining the standards in skydiving and jump aircraft operation requires a conscious everyday effort by skydivers, airplane owners and pilots. Skydiving airplanes are regulated under the Code of Federal Regulations Section 91 (known colloquially as Part 91), which are the general operating rules for nearly all personal flying, also known as general aviation. While Part 91 is less stringent than the regulations applied to scheduled airline service (Part 121) or commuter and on-demand operations (Part 135), there are additional provisions in Part 91 for commercial operators like skydive operators. Those provisions require additional aircraft inspections and require pilots to hold at least a commercial pilot certificate. Still, the difference between operating under Part 91 and operating under Part 135 is significant, but so is the expense. Additionally, a lot of the regulations imposed on 135 operators simply don’t make sense for skydiving airplanes. Most skydiving operators have very effective pilot-training and aircraft-maintenance programs based on a set of well-established standard operating procedures, so Part 91 works well. But operators must put proper safety standards in place and follow them closely.

The safety record of jump airplanes has improved somewhat over the past 25 years. Since 1995, there have been anywhere from four to 21 jump-plane accidents per year. The most fatalities per year in that time frame was 27 (1999) and the least was zero (2017). Although it is hard to make an accurate comparison, the jump-plane-accident rate appears to be about on par with the rest of Part 91 aviation, which includes flight instruction, banner towing, agricultural spraying and a host of other aviation activity.

While many skydiving operators around the country have learned from the mistakes of the past and developed very professional programs for aircraft maintenance and pilot training standards, the accident records show that there is still room for improvement. The challenge is preventing normalization of deviance from creeping in.

The West Point crash was a tragic event that forever changed the lives of 12 families and left hundreds of friends in shock for months. Normalization of deviance played a large part in that accident. It is easy for airplane owners, pilots and jumpers to let safety standards slip, which can lead to dangerous situations. Developing a solid set of standard operating procedures and sticking to them helps ensure safety levels remain as high as possible.

About the Author

About the Author

Jim Crouch, D-16979, was a jumper at Skydive Westpoint Inc. at the time of the Queen Air crash, and it took his life in strange and unexpected directions. Almost five years after the crash, he became the owner of the skydiving school that Dave Ropp and Ruth Sondheimer—who both died in the crash—started at West Point. He also became USPA Director of Safety and Training, following in the footsteps of Ches Judy, who also died in the crash. Crouch said, “The lessons learned from that day are as valuable as they were painful.”