In 2021, there were 10 total civilian skydiving fatalities in the United States. This is the lowest annual number of fatalities recorded since record keeping began in 1961. Way back in 1961, there were 14 fatalities while the level of skydiving activity was a tiny fraction of what it is today. The annual number of fatalities peaked in the late 1970s before beginning a slow decline. While the fatality numbers were decreasing over the years, the activity level of skydiving was increasing. Skydiving has been the only general aviation activity that has been able to reduce fatalities while at the same time greatly increasing the level of activity. When the numbers are placed into a rate index, it is easy to see just how much progress has been made in reducing the risks of making a skydive.

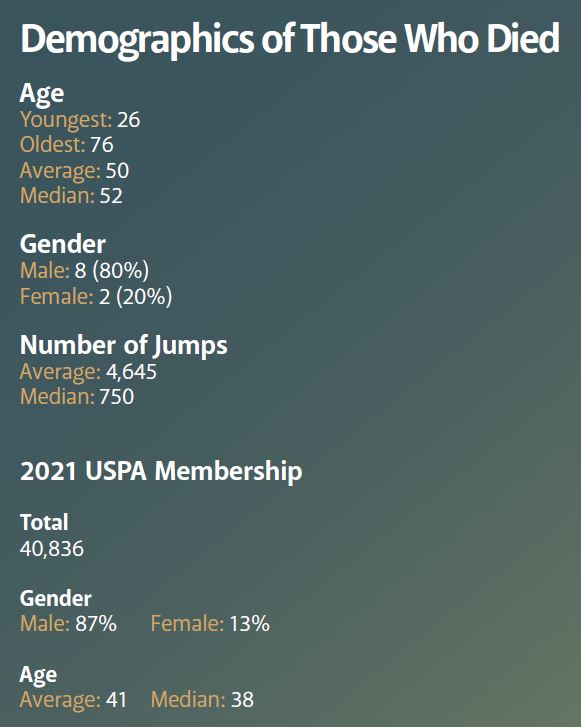

Even factoring in the curveball of a worldwide pandemic during the past two years, skydiving’s fatality rate has plummeted. Although jump activity slowed in 2020, most drop zones reported that the number of jumps made in 2021 (based on survey results, an estimated 3.57 million) was on par with what it was before the virus hit. That means with 10 fatalities in 2021, the fatality index was 0.28 deaths per 100,000 jumps, the lowest it has ever been.

Though the number of skydiving fatalities did decline gradually over the past four decades, the last four years specifically have seen the skydiving industry drastically reduce the annual fatality total. Thanks to constant testing and development, modern skydiving gear is safer and more comfortable than ever before. Thanks to the tireless work of coaches, instructors and examiners in the field, skydiving students across the country are benefitting from professional, quality training that produces skilled and knowledgeable A-licensed skydivers. Thanks to drop zone operators and Safety and Training Advisors, DZs have continued to create a culture of safety that promotes smart and safe skydiving practices. Along with all that effort, the most credit goes to the thousands of skydivers who take to the skies each weekend and place an emphasis on safety.

Although some years have missing data regarding student fatalities, 2021 was most likely the first year since 1961 in which no skydiving students died. This is a phenomenal achievement, especially when you consider that in 1976 alone there were 23 student fatalities. In the past decade, there have been anywhere between one and five student fatalities each year.

For the sixth year in a row, there were no fatalities in the no-pull category, and seven years have passed without a fatality in the low-pull category. Between the widespread use of automatic activation devices and higher main parachute activation altitudes, we’ve all but eliminated low- and no-pull fatalities, which used to be a significant segment of the annual total.

On the following pages, you will find the 2021 fatalities listed by category, followed by the number of fatalities in that category and the percentage of 2021 fatalities that number represents. For comparison’s sake, following that in parenthesis is the percentage of the total fatalities in that category over the last 20 years.

Landing Problems

5—50% (2002-2021—33.96%)

The landing problems category is comprised of three subcategories: non-turn related, intentional low turn and unintentional low turn. Although the fatalities in the main category all involve the failure to safely land a properly inflated main parachute, the subcategories distinguish between the causes of those failures, each of which involve distinctly different training and education solutions. Fatalities that fall into the non-turn-related category usually involve a jumper striking an object on the ground such as a building or trees. When a jumper strikes the ground in a steep descent while making a turn under a parachute at a low altitude for an attempted high-speed landing, it falls into the intentional-low-turn category. When a jumper dies while making a low-altitude turn to face into the wind or avoid another parachute or obstacle on the ground and strikes the ground in a steep descent, it falls into the unintentional-low-turn category.

Non-Turn Related

1—10% (2002-2021—11.48%)

• This jumper was 42 years old, had two years of skydiving experience and had completed an estimated 500 jumps. After an uneventful freefall and initial parachute descent under a 150-square-foot parachute loaded at 1.36:1, he began flying his landing pattern. While on his crosswind leg, he found himself higher than planned for his turn to final. He then extended his crosswind leg, eventually making a turn greater than 90 degrees onto his final leg to head back toward his planned landing spot. Once the turn was complete, he realized he was on level with other jumpers landing in the same area. Investigators believe he was focusing on the other parachutes instead of keeping track of his own descent. He then pulled down on both front risers, most likely in an attempt to get below the other jumpers. This maneuver increased his forward speed and descent rate, and he struck the ground while still in a steep dive with the front risers pulled down. He was transported to a local hospital and died a few days later.

What This Can Teach Us

Historically, the two most likely places a skydiver will encounter parachute traffic are right after deployment and below 1,000 feet above the main landing area while preparing to land. One of the best ways to ensure clear airspace during landing is to adjust your parachute descent prior to entering the landing pattern. If there are multiple groups in the airplane, protecting your airspace becomes more complex during your descent because of the various opening altitudes and wing loadings of the other jumpers. Once your parachute is open and flying properly, your immediate task should be to assess the traffic situation and adjust your descent so that you can fly your landing pattern in clear airspace with as few nearby parachutes as possible.

Although a turn was not the cause of this fatality, jumpers should remember that the chances of colliding with another parachute increase during turns. Always look around (to both sides, below and behind yourself) before initiating a turn to avoid colliding with or finding yourself on the same level as others. Jumpers should not adjust their descent rates to avoid being on level with other jumpers in the landing pattern. However, if it is unavoidable, it is better to fly in brakes to slow your descent rate (keeping an eye out for those above and behind you) rather than increase your descent rate by using front-riser input.

If the main landing area is too congested for a safe landing, the best plan is to choose an alternate landing area. Sometimes it is best to land in a clear area that is farther away from the other parachute traffic. If you do find yourself landing near other parachutes and you are flying in the same direction, maintain a parallel path with the other parachutes by making very small corrections while dividing your attention between the nearby traffic and your landing spot. Landing with a level wing and flaring at the proper altitude is still the landing priority, even with other parachutes nearby.

Unintentional Low Turn

1—10% (2002-2021—8.13%)

• This jumper was 28 years old and had been skydiving for two years. He had accumulated a total of 72 jumps. After an uneventful freefall and initial canopy descent under a 167-square-foot parachute loaded at 1.2:1, he was at approximately 150 feet directly over his intended landing area. He then initiated a 360-degree turn to avoid overshooting his intended landing area. He struck the ground at a high rate of descent without flaring the parachute. He was killed by the hard landing. Investigators believe he was focused on landing in his intended target area, which was a pea-gravel pit. There were large open areas available for him to continue flying in a straight direction for landing.

What This Can Teach Us

Many new jumpers make landing accuracy a priority at the end of their skydives, which can be a challenge when they are also trying to figure out the descent paths of their parachutes. New jumpers also tend to feel a self-induced pressure to land close to the target to complete the landing accuracy requirements for higher licenses. When a jumper ends up in the wrong spot at the wrong altitude, it can lead to confusion and panic. It is always better to continue flying the parachute in a straight line toward a clear area than to make a low turn to try to land closer to the intended landing spot. Landing far away from your intended landing area still serves as a valuable lesson, and you can apply corrections during the next jump to improve accuracy.

Intentional Low Turn

3—30% (2002-2021—14.35%)

• A 26-year-old jumper with three years of experience and 430 jumps was jumping as a candidate during an Accelerated Freefall Instructor Certification Course. He was jumping a 135-square-foot elliptical parachute at a wing loading of 1.37:1. The freefall and initial parachute descent were uneventful. At approximately 400 feet, this jumper pulled down on both front risers to increase his descent rate and forward speed, then let up on his left riser to initiate a 90-degree turn to the right toward his intended landing spot. Witnesses on the ground observed him in a steep descent with both arms all the way up as he rapidly approached the ground at a 45-degree angle. He then pulled his toggles down to begin flaring the parachute, but he struck the ground at a 45-degree angle at an estimated 50 miles per hour. He received immediate first aid and was taken to a local hospital where he died a few hours later from the injuries sustained in the hard landing. Despite the jumper’s high wing loading for his low experience level, investigators reported that this jumper was usually a conservative canopy pilot who normally performed 90-degree turns for his final approach. He had attended a high-performance canopy course the previous weekend.

• A 35-year-old jumper with seven years of experience and an estimated 1,000 jumps made a solo jump with a borrowed, demonstration model 87-square-foot main parachute. After an uneventful freefall and initial descent under the parachute, he initiated a turn to attempt a high-performance landing. His body struck the ground at the same time as the nose of the parachute while it was still in a steep, diving descent. He was airlifted to a local hospital but died before arrival. Very little information was provided for this fatality. It was his first jump on this parachute, and he reportedly did not tell anyone at the drop zone that he was jumping it. He also apparently misrepresented his experience level to obtain the demo parachute. The manufacturer and wing loading were not reported.

• A 31-year-old jumper with five years of experience and more than 600 jumps exited at 6,000 feet and deployed his main parachute immediately. He was jumping a 135-square-foot parachute at a wing-loading of 1.8:1, which, due to his experience level, indicates that he had rapidly downsized. After an uneventful initial canopy descent, a witness on the ground reported that he initiated a “very low” turn to final approach that placed him flying downwind. His hands were fully up toward the rear risers, and he did not make any attempt to flare before he struck the ground in a steep descent at nearly the same time as the parachute. He received immediate first aid, but he died soon after arriving at the hospital. His autopsy revealed that his blood alcohol level was 220 mg/dL, or nearly three times the limit to legally drive a motor vehicle in most states.

What This Can Teach Us

Many fatalities in the intentional-low-turn subcategory over the past 20 years were very similar and involved:

- A male jumper with 1,000 jumps or fewer

- Rapid downsizing to a parachute too small and advanced for the jumper’s skill level.

- Initiation of a low turn to attempt a high-performance landing with little experience or training

-

Oddly, the reports describing these fatalities often included comments that the jumper was considered a conservative canopy pilot.

Despite the additional risks of performing high-performance landings under small, highly loaded parachutes, many jumpers still want to attempt them. The risks can be reduced by working with experienced canopy coaches and advancing slowly toward jumping smaller parachutes. Even so, the risks of a severe injury or death from a misjudged turn near the ground are substantial.

Another issue leading to this type of fatality is the widespread acceptance of jumpers rapidly downsizing to smaller parachutes. Safety and Training Advisors, examiners, instructors and drop zone operators should all work together to create a positive safety culture that encourages jumpers to spend more time mastering their current parachutes before moving to smaller, more advanced designs. Flying a parachute to a successful high-performance landing requires a lot of practice and skill and nearly flawless eye-to-hand coordination. While initiating a turn to induce speed for landing, a jumper must make split-second decisions to manage the energy of the recovery arc and level the parachute across the ground at the correct altitude. The pros make it look easy, but it takes a lot of time and practice and a slow progression to learn the craft.

In addition, one of the jumpers was under the influence of alcohol, which greatly affects mental acuity and physical coordination. At least two jumpers thought they smelled alcohol on him before the jump. If you suspect a jumper is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, pulling him off the load and sorting things out on the ground is the right thing to do.

Incorrect Emergency Procedures

1—10% (2002-2021—6.22%)

A fatality falls in this category when a jumper is faced with a malfunction that requires them to perform emergency procedures but they do not respond correctly to the situation.

• This jumper was 57 years old and had started skydiving approximately 35 years earlier, accumulating more than 2,000 jumps. She had reportedly returned to the sport nearly two years before this incident after having taken a long absence from jumping. She had completed approximately 40 jumps since her return to skydiving.

Toward the end of a 9-way formation skydive, this jumper had a minor collision with another jumper that resulted in the formation breaking apart. Other jumpers in the formation observed her tracking away at an altitude higher than the planned breakoff altitude, but no one witnessed her parachute deployment. Two experienced jumpers on the ground then observed the jumper at approximately 1,000 feet with both the main and reserve canopies fully open and flying in a downplane (both parachutes diving toward the ground). She was apparently able to stop the downplane by steering the parachutes into a side-by-side configuration, which greatly slowed her descent rate. However, at approximately 200 feet, the two parachutes returned to a downplane. She was unable to regain control and descended at high speed until she struck the ground. First responders attempted first aid, but she died at the scene from the hard impact.

What This Can Teach Us

As with most fatalities, several factors contributed to this fatal outcome. There were also several opportunities for the jumper to change the end result with a different response. It was not reported if this jumper had recently reviewed emergency procedures. Frequent review and practice of emergency procedures helps jumpers respond correctly during an actual malfunction. It is important that the review includes responses to a pilot chute in tow, as well as the various configurations encountered during two- parachutes-out scenarios.

Section 5-1 of the Skydiver’s Information Manual lists two different responses for a pilot-chute-in-tow malfunction: either pull just the reserve ripcord or pull the cutaway handle then pull the reserve ripcord. Both procedures can work successfully, and both procedures will require different actions in the event the main parachute deploys after the reserve inflates. It is critical that every jumper fully understand each procedure, decide ahead of time which procedure to use and practice it frequently. A more detailed examination of pilot-chute-in-tow considerations can be found in the article “Decisions, Decisions—Responding to a Pilot Chute in Tow” in the March 2021 issue of Parachutist.

Additionally, the Parachute Industry Association performed a study of dual deployments in 1997 that provides valuable information for every jumper. Even though the study is now more than 25 years old, the information is still relevant. Regarding downplanes, the study states, “Being in a dual-square situation calls for quick evaluation and quick action. A downplane plummets out of the sky at a high rate of speed. The best thing to do in a downplane situation is to disconnect any [reserve static line] and cut away the main canopy.” The full report is available at pia.com/wp-content/uploads/tb-261.pdf.

Medical Problems

30% (3) (2002-2021—8.6%)

When a jumper suffers an obvious medical problem during a skydive—whether mental or physical—the fatality falls into this category. Two subcategories comprise the main category: mental health issues (generally suicide) or physical health issues (e.g., a heart attack or stroke). In 2021, there was one suicide and two heart-health-related fatalities during skydives.

Mental-Health Related

1—10% (2002-2021—2.63%)

• A 74-year-old jumper with approximately 17 years of experience and an unreported number of jumps made a 3-way formation skydive with two other jumpers. After an uneventful freefall and initial parachute descent, he pulled his cutaway handle at approximately 400 feet. At some point before he pulled the cutaway handle, he had disconnected his reserve static line. Witnesses on the ground observed him fall behind a row of trees. Investigators discovered that this jumper had cleaned out his desk at work as if he were not returning. Although USPA received very little information about this fatality, the information provided indicated that suicide was the cause.

Physical-Health Related

2—20% (2002-2021—5.98%)

• A 76-year-old jumper with more than 45 years of experience and more than 20,000 skydives was part of a 7-way formation skydive from a Cessna Grand Caravan that was also carrying several other groups. The freefall and initial canopy descent were uneventful. During the landing pattern, this jumper was flying a base leg toward the south, which had him flying directly toward another canopy that was headed in the opposite direction at the same altitude. The jumper who was flying north expected the other jumper to turn toward final approach, but he did not. The second jumper finally turned his own canopy toward final approach as the two parachutes narrowly missed each other. However, the main parachute bridle of the turning parachute snagged the helmet of the other jumper. The turning parachute briefly collapsed and reinflated with no heading change, and that jumper landed uneventfully. The other jumper’s parachute began a slow turn toward the ground, and he landed hard without flaring the parachute. He was declared dead at the scene.

The autopsy played a key role in this investigation. The coroner determined that this jumper had died from a heart attack, which explains why he was unresponsive while flying his base leg. Additionally, he had severe coronary artery blockage and other unrelated health issues. When the pilot chute of the other jumper caught on the chin strap of his helmet, it quickly pulled his head to the side and severed his spine at the level of C5-C6, and he suffered multiple fractures throughout his body from the hard landing. Blood tests also revealed a presence of THC, indicating use of marijuana immediately before the skydive. Although the level of THC likely affected his mental and physical acuity during the jump, it could not be determined if it had any effect on his other medical issues

• A 73-year-old jumper with more than 50 years of experience and more than 16,000 skydives was part of a 3-way formation skydive that was uneventful during freefall, breakoff and parachute deployment. Witnesses on the ground observed the jumper hanging limp in the harness under his fully inflated main parachute as it overflew the drop zone. He landed in an intersection of a roadway without flaring the parachute. First responders reached him immediately, but he had no pulse, and they declared him dead at the scene. A review of footage from the jumpers’ video camera showed that the main parachute opened normally and that the jumper initially reached up to release his brakes but then dropped his arms and had no response for the remainder of the parachute descent. The autopsy revealed that this jumper had extensive coronary artery disease and that he had suffered a heart attack. He may have still been alive but unconscious during the descent, and his cause of death was listed as blunt-force trauma to the head and neck, which occurred from landing without flaring the parachute.

What This Can Teach Us

Suicide continues to be a significant cause of death in the United States. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, suicide accounted for 47,511 deaths in 2019. This is more than twice the rate of death by homicide at 19,141. It is the number two cause of death for those who are 34 or younger, and the 10th largest cause of death for people of all ages. Death by suicide during a skydive has been a small but relatively consistent percentage of the annual total each year, and at least 14 people have died by suicide while skydiving since 1999. Help is available for suicide prevention through many local and national mental health services. If you know of someone struggling with depression or suicidal thoughts, encourage them to get the help they need. Unfortunately, it often comes as a complete surprise when someone commits suicide, and there is no chance to help them before they are gone.

Heart disease is responsible for about one quarter of all deaths in the United States, with approximately 659,000 deaths each year. It is found in approximately 12% of the population. When you factor in all forms of cardiovascular disease such as coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke and high blood pressure, that percentage jumps to 48% of the population. So, it is only natural that a percentage of skydivers also suffer from some form of heart disease, particularly older jumpers. Skydiving adds stress to the body, even for licensed skydivers with a lot of experience. It is wise for all skydivers to keep a close eye on their health, especially those who are over age 40 or who have a family history of cardiovascular disease or other health problems. Skydiving deaths attributed to health problems have been a small but significant percentage of the total fatalities over the years. There is usually at least one skydiving fatality per year attributed to a medical problem.

Cutaway and Low Reserve Deployment

1—10% (2002-2021-5.02%)

A fatality is placed in this category if a jumper releases the main parachute and deploys the reserve but there is insufficient altitude for the reserve to inflate before the jumper strikes the ground.

• A 59-year-old jumper with 25 years of experience and approximately 1,000 jumps was making a solo skydive from 6,000 feet, intending to land on a farm owned by her family. The pilot was also a skydiver, and he reported that he did not see anything unusual about her deployment but that the left side of her parachute may not have been inflating properly. She released the main parachute at an unreported altitude and deployed the reserve, but there was not enough altitude for the reserve to inflate. She was declared dead at the scene.

What This Can Teach Us

What This Can Teach Us

This jump took place on a private farm and very little information was provided regarding the details of the jump. The jumper had not jumped in the previous two years but had practiced emergency procedures before the jump (although what that practice entailed was not reported). The main parachute was recovered from a tree and several lines on the left side were broken, which probably occurred during the deployment. The broken suspension lines indicate that the parachute most likely opened hard, which may have stunned the jumper and delayed her decision to release the main parachute and deploy the reserve. It is hard to say if the long layoff played a factor in the delayed cutaway. Reportedly, the jumper was heavyset and struggled to get out of the door of the Cessna 182. However, it is not possible to determine whether her weight was a factor in the hard opening of the main parachute or the delay in cutting away the main. It was not reported whether the container was equipped with a reserve static line. However, the use of an RSL can help ensure the reserve parachute activates as quickly as possible following a cutaway of the main.

The good news is that 2021 set a record low for fatalities, continuing the trend of very low annual totals that began in 2018. There were also no student fatalities—the first time this has occurred in the modern era (if ever). Thanks to the collective effort of equipment manufacturers, drop zone operators, instructional rating holders and the jumpers themselves, the sport of skydiving is moving in a positive direction, and it is safer than ever before.

But even with tremendous progress in the area of safety there is still work to do and room for improvement. Skydivers began flying high-performance parachutes about 30 years ago. During those three decades, parachute designs have vastly improved, and jumpers are now flying smaller and faster wings than ever before. Skydivers who want to pursue high-performance parachute flight have a vast array of training programs and information available to them to help reduce the risks as much as possible. Despite that, we needlessly lose anywhere from one to five jumpers a year from badly misjudged landings. In almost every case, it is someone who was unprepared and untrained flying a parachute way too advanced for their skill level. Due to the Dunning-Krueger Effect, the jumper often does not recognize their own lack of skill while rapidly downsizing to smaller parachutes. Every drop zone needs to create a strong safety culture that helps jumpers progress toward challenges at a reasonable rate and encourages them to take advantage of training and educational opportunities to reduce as much risk as possible. Whether your chosen discipline is formation skydiving, freeflying, wingsuiting or high-performance parachute flight, there are plenty of resources available.

The fatality numbers also don’t show the dozens of nearly fatal accidents that take place each year. Many skydivers have suffered life-altering injuries due to hard landings under small, highly loaded parachutes. Due to advances in first aid and a more widespread use of medical helicopter evacuations, jumpers who might have died from severe injuries are now surviving, but often with paralysis or other life-altering injuries.

2021 was a banner year for skydiving safety. Millions of skydives ended safely, including those made by hundreds of thousands of solo and tandem students. With a lot of effort and a little luck, we might just see a year with no fatalities coming soon. And that would be a wonderful thing, for sure.

About the Author

About the Author

Jim Crouch, D-16979, was USPA Director of Safety and Training from 2000-2018.