Photo above: Sarah Roberson wears her skydiving gear during a maternity photo shoot. Photo by Eric Salas.

Let’s be honest, it’s not easy to facilitate the creation, growth and birth of a new life. Any pregnant woman would agree: Pregnancy causes a lot of physical changes. Some changes start as early as the fifth week of pregnancy. Resting heart rate increases, the heart remodels and increases in size, lung space decreases as the growing fetus pushes the diaphragm up into the chest, and breathing rate increases to compensate for that change. The body’s center of gravity shifts forward with the growing belly and breasts, causing imbalance and instability. The pelvis tilts forward and joints become flexible and relaxed, preparing for the baby to pass. Energy needs increase by up to 500 calories a day by the third trimester.

Exercise in pregnancy is known to have a variety of benefits, including decreased rates of casarean sections, better postpartum recovery, prevention of excess gestational weight and reduced pregnancy complications of pre-eclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes and low birth weight. Current recommendations include performing at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise each week, spread over three days or more. Recommended activities include walking, swimming and cycling; however, most recommendations state that activities performed prior to pregnancy can likely be continued, with the exception of contact sports. While skydiving incorporates a great combination of strength training and cardiovascular exercise, it currently does not make the official accepted activity lists.

Despite the inherent benefits, many physical changes and associated symptoms can hamper performance during exercise such as skydiving. Nausea and vomiting in the first six to 12 weeks occur in 50-80% of pregnancies, and 20% of pregnant women experience these symptoms for 20 weeks or more. Fatigue affects nearly 90% of pregnant women. Swelling in the legs can lead to significant discomfort, and may worsen with compression of the large blood vessels by tight leg straps during canopy flight. Likewise, tight chest straps can become uncomfortable with enlarging breasts.

Pregnant women are increasingly prone to musculoskeletal injuries, as joint laxity and enhanced flexibility increases the possibility of sprains and strains. Imbalance from a shifting center of gravity increases the chance of falls, which is the most common type of injury in pregnancy. When injured, pain control options are limited, as little outside of acetaminophen (brand name: Tylenol) is considered safe in pregnancy. Pelvic girdle pain from changes in the pelvic musculoskeletal system causes issues in up to 50% of pregnancies, and is severe enough in 20-25% to seek medical care.

Weight gain itself can cause issues, as the typical 12-20kg (26-44 pounds) of increased weight can affect wing loading up to 25%, increase fall rates and change the basic fit of the harness and jumpsuit. Some loss of bladder control also complicates many pregnancies and was found to occur in 28-80% of pregnant elite athletes, most commonly in high-impact activities (i.e., it may be normal to experience minor urine leakage when the parachute canopy opens). Pelvic organ prolapse (imagine an old school VCR ejecting a cassette … and the cassette is the cervix) can also complicate some pregnancies and postpartum periods. This was found to be 2.5 times more likely in pregnant female military cadets who attended paratrooper training than those who did not.

So, what is actually known about specific risks of skydiving during pregnancy? Short answer: very little. The primary risks to pregnancy during skydiving involve three major categories: trauma, hypoxia and heat.

Trauma in Pregnancy

Most data from maternal trauma is based on motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), and typically involves pregnancies greater than 20 weeks. In the first trimester, the fetus is well protected by both the thick-walled uterus and pelvic bones. In the second trimester, the fetus begins to grow out of the pelvis but is relatively protected by the large amount of surrounding amniotic fluid. In the third trimester, there is substantially less protection as only the abdominal musculature and a thin uterine wall guard the fetus.

Studies of MVAs involving pregnancies over 20 weeks of gestation generally demonstrate increased complication rates of preterm birth, placental abruption and stillbirth. Higher rates were observed after each subsequent MVA. Placental abruption usually occurs due to sudden deceleration causing a shearing force between the placenta and uterus wall, leading to separation and bleeding. Overall rates are still generally low, and less than 1% of pregnant accident victims experience significant placental or uterine injury.

Rates of placental abruption appear to significantly increase at 28-30 weeks, reflecting heightened risk after that time. Abruption has a high incidence of perinatal mortality, and even at the optimal gestation of 40 weeks there is a 19-fold increase in fetal death rates. The severity of trauma matters less in late term pregnancies, as even minor trauma can cause pregnancy complications.

But what about early pregnancy? Studies are inconclusive on the effects of trauma on early pregnancy, and the fetus is generally thought to be well protected. Some studies attempt to associate first trimester trauma to increased rates of fetal deaths in later trimesters, but linking this causality is difficult given a variety of confounding factors (i.e., extra or unaccounted for factors). For most other studies, excluding maternal deaths, loss of a fetus in the first trimester could not be explained by trauma and was unlikely to be related.

I know what you’re thinking: There’s a big difference between typical skydiving trauma and car crashes! Well, a better comparison might be injuries from falling, but unfortunately there is even less data about falls in pregnancy. A study out of the state of Washington looking at 700 pregnant females hospitalized after falling found an associated increased risk of preterm labor, placental abruption, induction of labor, hypoxia and fetal distress. However, take these findings with a grain of salt, as the overall risk of these complications was still very low. The study involved mainly third-trimester pregnancies and specifically hospitalized mothers, which means as a group they had more severe injuries. A recent study out of Taiwan looked at traumatic injuries in pregnant patients, and any association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. It was found that when confounding factors were excluded, patients who had an emergency room visit for a traumatic injury had minimally increased odds of an adverse pregnancy outcome. However, hospitalization for a traumatic injury, especially repeat hospitalizations, appears to significantly increase the odds of premature delivery. Overall, fetal harm in early pregnancy seems very unlikely to occur if there is no maternal loss of consciousness, significant bruising or other reason for hospitalization.

The greatest risks from skydiving in later pregnancy include the rapid deceleration that takes place during canopy opening, as well as the deceleration and direct abdominal trauma from impact with the ground or other jumpers. The belly-to-earth position typically yields a vertical fall rate of 120 mph, rapidly slowing to a canopy fall rate of approximately 17-21 mph. A hard opening can cause sudden deceleration and potential shearing injury similar to that experienced during an MVA, increasing the risk of placental abruption. Direct abdominal trauma from a hard landing or impact with another skydiver can lead to uterine, placental or direct fetal injury and increase the chance of pregnancy complications.

Hypoxia and Altitude Exposure in Pregnancy

Pregnant females living at high altitudes have increased rates of miscarriage and pregnancy complications, but little is known about short-term exposure to high altitude in pregnancy. The theoretical concern is that both exercise and hypoxia decrease blood flow to the uterus and contribute to decreased fetal oxygen supply, so current recommendations are to limit training at altitudes above 1,500-2,000 meters (4,921-6,561 feet). However, studies looking at shorter-term exposure to high altitude only minimally support this recommendation. One such study involved nearly 600 pregnancies exposed to activities at altitudes over 2,440 meters (8,000 feet). While only two women reported skydiving as their activity, 30% participated in downhill skiing, 20% rock climbing, 12% mountaineering and 24% mountain biking. The primary finding included increased rates of preterm labor and oxygen use by the newborns in women who were exposed to high altitude during pregnancy. However, the overall rate of preterm labor was still lower than average for all pregnancies, and there was no increased rate of NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) admissions, meaning these newborns generally did not tend to be more sick. Therefore, the actual importance of this increased rate is questionable. There was also no increase in rates of miscarriage, preeclampsia, eclampsia, C-sections, second- or third-trimester bleeding, placental abruption or need for induced delivery. Additionally, the “short-term” exposure for these women was a whopping average of 13 days at high altitude, and yet they still experienced low rates of complications. So any effect that minutes spent during a climb to altitude would have on a pregnancy is likely minimal. The one exception may be mothers with underlying heart or lung issues, who would typically experience increased stress at high altitudes.

Environmental Heat in Pregnancy

Lastly, increased core body temperature greater than 39.4 degrees Celsius (103 degrees Fahrenheit) is known to affect neural-tube development in early pregnancy and increase the risk of fetal abnormalities. Studies looking at exercise in pregnancy have found that 60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise did not lead to core temperature elevations above 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit). However, this study was not performed in a hot environment, so the results cannot be applied directly to our population. While jump planes can get pretty darn hot, the safest strategy is to stay cool between jumps and minimize time spent doing strenuous exercise in overly hot environments. Keep well hydrated with cool water and stay in the shade or cooler areas when waiting in the loading area.

Six-month-old Kubik Stengl cuddles up in the perfect bassinet.Photo by Roman Stengl.

Skydiving in Pregnancy

It is important to find an obstetrician whom you can talk to frankly about the risks and benefits of continuing to skydive. Looking at most, if not all, guidelines regarding the do’s and don’ts of exercise in pregnancy, skydiving is listed as an activity that should be avoided. This is the most conservative option, but those of us who skydive recognize not only the physical benefits but also the psychological and emotional benefits of a little “air therapy.” When talking to your doctor, put skydiving into terms they can understand: It is an activity that includes an unpressurized ride to about 14,000 feet; less than 10 minutes is typically spent above 8,000 feet; there is a period of freefall with an opening shock of canopy deployment and a landing that is similar to jumping off a regular chair but may include a butt slide or roll.

Assuming not every female wants to stop skydiving when she finds out she’s pregnant, how can skydiving be made safer? First off, consider your skill level, accounting for not only jump numbers but also currency, recency and your wing loading. Do you tend to stand for most landings or do you find yourself performing many parachute landing falls? Are your landings the kind your grandma could handle, or do your knees and hips really feel the force of impact on landing? Consider jumping with a larger parachute to decrease your wing loading and partially soften landings. To decrease the force of canopy opening shock, you might also consider hop-and-pops (which also decreases your exposure to altitude and potential hypoxia). If you do go to altitude, try to be one of the first jumpers out of the plane to decrease your altitude-exposure time. Realistically, this is not the time to consider a new discipline like swooping or canopy formation skydiving that can increase your chance of injury. This is also not the time to push your weather limits. Taking risks to jump in marginal weather or wind conditions is a recipe for a nasty landing. You may also want to weigh the risks of jumping with larger groups or inexperienced jumpers, as both of these scenarios increase your risk of mid-air collisions or accidents. Avoid scenarios with prolonged exposure to exceptionally hot environments, and make sure to stay well hydrated. Keep snacking too. Remember, you have an extra, growing passenger who is stealing your blood sugar!

The decision of when to pause skydiving is a very personal one, but should include a conversation between the entire family and a trusted physician. At around 12 weeks, the pelvis no longer completely protects the uterus, and the risk of fetal injury increases. However, there is no clear measure for when trauma appears to significantly affect the health of a pregnancy, and some doctors recommend 20 weeks as an arbitrary cutoff for higher-intensity activities. Patients with pre-existing health conditions or already at high risk for preterm labor or other pregnancy complications should seriously consider taking a break from skydiving.

One of the biggest decision points will come from a deep look inward by the skydiver herself, assessing whether she will have significant self-blame for an early miscarriage or later pregnancy complications. Miscarriages are more common than most people think. With or without skydiving, the rate of miscarriage is nearly one in every five to six pregnancies. The majority of these miscarriages are due to chromosomal abnormalities that would not allow the fetus to grow and mature regardless of anything the mother did or did not do. However, even knowing this, some mothers may feel a sense of personal responsibility for any bad pregnancy outcomes that occur. This potential emotional weight may outweigh the benefits of continuing skydiving, and should be heavily considered throughout the entire pregnancy.

The decision of when to return to jumping after giving birth is also very personal. A C-section will require a longer recovery period as the body needs time to allow wound healing; most suggest about six weeks to recover. You may find you have to readjust your rig and possibly use a different jumpsuit to fit your new figure. Be extra careful when first getting back into jumping as your center of gravity and wing loading may not have returned to pre-pregnancy values. Whenever you decide to return, you and your new family will surely be welcomed with open arms. After all, getting to share our passion for the sky and the wonderful skydiving community with our children is priceless.

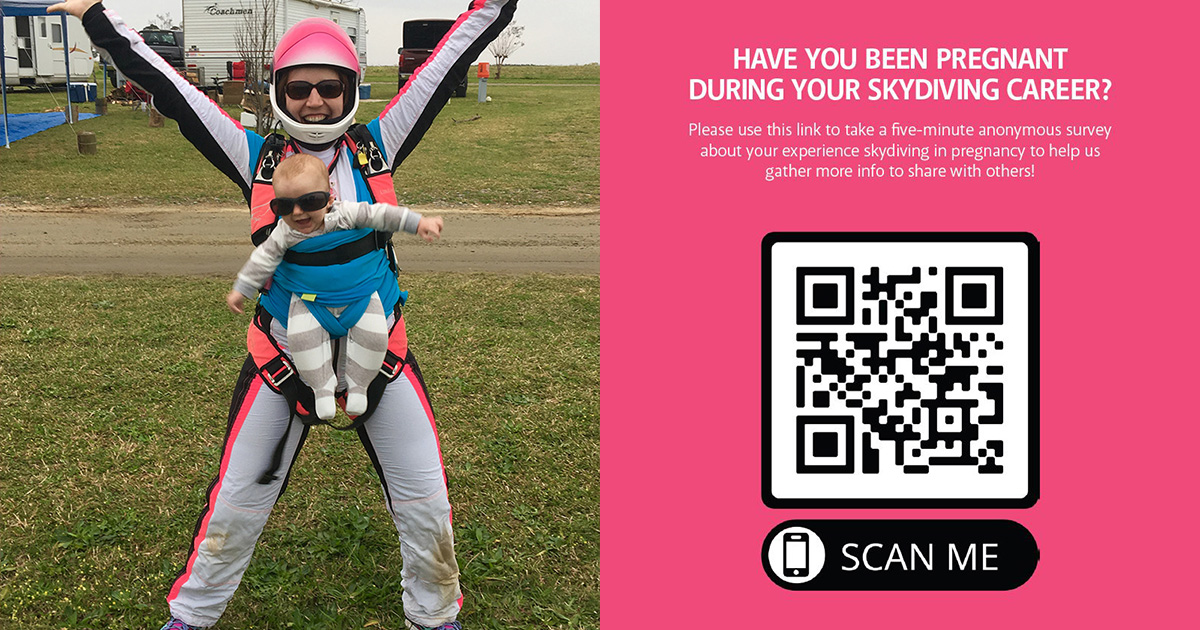

Five-month-old Archer Manning and his mother, Lindsay Manning, pretend to make a tandem jump together.Photo by Natalie Jenereski.

You can also access the survey by clicking here.

About the Author

About the Author

Laura Galdamez, M.D., C-50829, began skydiving in early 2020. She works as an emergency medicine physician in Houston, Texas; is a Fellow of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine; and worked on the medical team for the StratEx high-altitude balloon mission. She competes in 4-way formation skydiving on a team out of Houston called Non-Toxic.