Skydivers can learn a lot by understanding the causes of fatal incidents, but non-fatal incidents have just as many lessons to teach. Since 2019, in an attempt to determine where our sport’s safety and training standards need improvement, USPA has pushed for increased reporting of non-fatal incidents. To help, the USPA Board of Directors added information on incident reporting to Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 5-8.

In 2022, USPA received 307 incident reports, a 22% increase over the number of reports received in 2021. (Due to USPA’s publicity efforts, this likely represents a higher rate of reporting rather than a higher rate of incidents.) Of the 307 reports, 269 are included after removing fatal incidents (covered in “A Step Backward—the 2022 Fatality Summary by Jim Crouch in April’s Parachutist) and reports of non-fatal incidents that contained insufficient detail to be useful. Due to the large amount of data received, we’ve broken this article into two parts. Part one will cover landing incidents only, since they account for 58% of the total and provide many important lessons. Part two will appear next month and include the other largest categories.

The Injury Severity Index (ISI)

For this report, USPA categorized the severity of the injuries sustained during incidents by developing an Injury Severity Index (ISI) that uses a scale of 0-5.

0—No injury

1—Soft-tissue injury typically requiring only local first aid

2—One broken bone or multiple breaks of a single bone or joint

3—Multiple broken bones

4—Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury

5—Fatal (not included in this report)

In the following pages, we’ve categorized the non-fatal incidents by primary cause, followed by the percentage of overall incidents that the category represents. In the absence of adequate historical data on non-fatal incidents, this report compares 2022’s percentages to the average of three years, 2019-2021.

Landing Problems–156, 58% (2019-2021–45%)

Three subcategories of landing problems–each requiring different areas of training to prevent–compromise the overarching category. These subcategories of landing problems are:

- Intentional low turns: intentional high-performance maneuvers for landing. These usually involved a jumper who initiated a high-performance turn at an altitude too low for the parachute to return to straight-and-level flight before reaching the ground.

- Unintentional low turns: unplanned low turns, usually to avoid other parachutes in the air or obstacles on the ground.

- Non-turn-related: includes improper landing techniques, landing on obstacles or encountering other hazards (such as deep water) while under a properly functioning parachute.

Intentional Low Turns–16, 5.9% (2019-2021–6.3%)

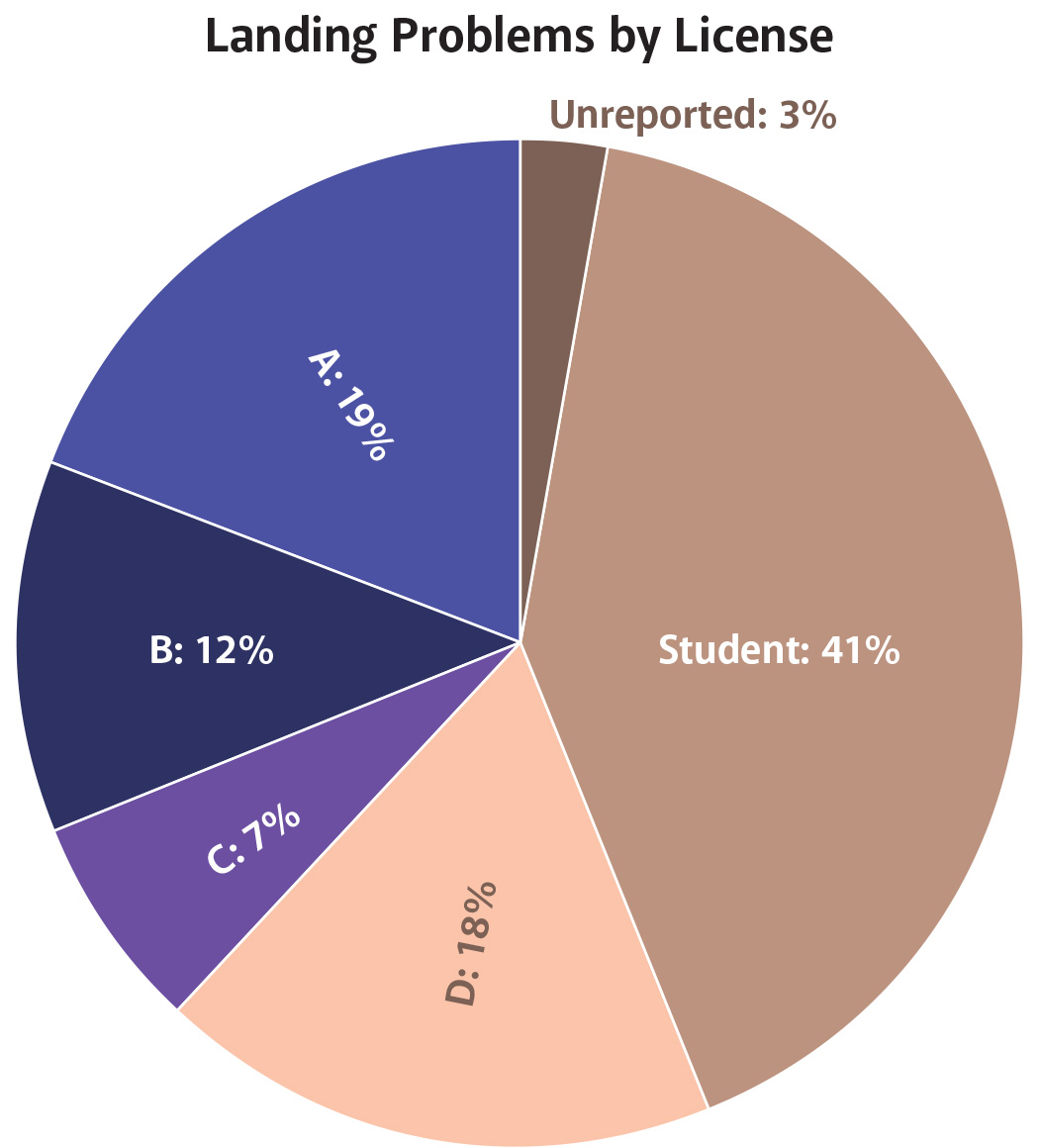

Of the 16 reports in this category, one involved an A-licensed jumper, one involved a B-licensed jumper, three involved C-licensed jumpers and 11 involved D-licensed jumpers. The A-license and B-license holders loaded their canopies at 0.9:1 and 0.96:1, respectively. The report for the A-licensed jumper did not contain any injury information. The B-licensed jumper sustained a compression fracture to the lower back but was released by the hospital the same day. Even without injury information on one of the jumpers this year, data from 2021 shows that severity of injury increases with wing loading, so in all likelihood their conservative canopy choices spared them greater harm from making an ill-advised low turn.

Out of the 11 D-licensed-jumper incidents, three did not receive an injury severity score. In one—a jumper who knocked down a spectator following a 270-degree turn and plane-out—the report did not contain injury information for either party. The other two involved tandem jumps in which the instructor violated the USPA Basic Safety Requirement prohibiting turns of more than 90 degrees below 500 feet. In one of the cases, the instructor stabbed out of the turn with toggles. The pair landed hard, but neither jumper suffered severe injuries. In the other, the tandem pair hit the ground hard at the end of the recovery arc of a 270-degree turn, with the student hospitalized after suffering injuries described simply as “severe” and the instructor walking away with minor bruises and scrapes.

Note: If a member submits an incident report anonymously, USPA cannot take action for BSR violations contained in it. Jumpers who wish to report BSR violations should do so by emailing safety@uspa.org.

The ISI rating for the remaining 11 intentional-low-turn incidents was 3.0. In each, the jumper broke a bone or herniated a disc, with most reporting multiple broken bones. On average, the three C-licensed jumpers had 478 jumps, a wing loading of 1.56:1 and an ISI of 3.3. The D-licensed jumpers averaged 2,682 jumps, a wing loading of 1.9:1 and an ISI of 3.2.

These results are unusual, since those who load their canopies more heavily generally suffer more severe injuries. This could suggest that less-experienced jumpers tend to make more tragic mistakes or it could be just an anomaly based on the small sample size. Also relevant is that these statistics excluded fatalities, and eight of the 24 intentional-low-turn incidents reported in 2022 were fatal. Excluding tandem incidents, the average wing loading for D licensed jumpers who died in this category was 2.2:1, with an ISI of 5. So, for all intentional low-turn incidents (fatal and non-fatal), the D-licensed jumpers loaded their canopies at an average of 2:1 and had an ISI of 3.9.

What this tells us is that when jumpers under small, fast canopies make high-performance maneuvers for landing, the tolerances are very unforgiving and the consequences of mistakes are severe. It’s also worth bearing in mind that one wing loading does not fit all D-licensed jumpers. The experience level of these D-licensed jumpers ranged from 597 jumps to 8,000 jumps. USPA recommends a maximum wing loading of 1.4:1 until the jumper has 1,000-plus jumps. And all jumpers must practice more-advanced techniques under less-aggressive canopies and learn how to get the best performance out of those canopies before downsizing.

Unintentional Low Turns–8, 3.0% (2019-2021–6.6%)

Two jumpers died making unintentional low turns in 2022, and 87% of the eight jumpers who survived unintentional-low-turn incidents last year reported breaking at least one bone. The Injury Severity Index for this category is 2.85, slightly above the 2.76 ISI of the intentional-low-turn category. Students and A-licensed jumpers accounted for 50% of incidents reported in this category in 2022, and D-licensed jumpers accounted for the other 50%. B- and C-licensed jumpers were unrepresented. The A-licensed jumpers had an average wing loading of 0.9:1 and an ISI of 2. In contrast, the D-licensed jumpers, who loaded their parachutes more heavily (an average of 1.4:1) had more severe injuries (an ISI of 2.6).

Low-experience jumpers are prone to making unintentional low turns, and often the jumper has recently downsized. In 2022, some of the low-experience jumpers experienced landing pattern complications in higher-than-student-level winds and turned low to avoid obstacles. As winds get higher, traffic patterns are more unpredictable and turbulence can be more violent and roll out farther from obstacles, so the skill required to land rises exponentially. Although jumpers have no wind restrictions after becoming A licensed, jumpers should set personal wind limits that they only gradually increase as their skills improve.

It’s also possible that low-experience jumpers stop or cut back on rehearsing their emergency procedures (including low-altitude emergencies) after becoming licensed, and it’s finally catching up to them. Instructors can help mitigate these problems by emphasizing low-altitude emergencies during student training and by reminding their graduates to continue rehearsing them for their entire skydiving careers.

Non-Turn-Related–134, 49% (2019-2020–32%)

There were 136 reports of non-turn-related incidents in 2022, and only two were fatal, indicating that even if you encounter a problem, most straight-in approaches are survivable. Most of the jumpers had low experience levels, with just a handful being very highly experienced. (The jumpers had an average of 669 jumps but a median of only 53.)

Although landing in a straight line with a level wing remains the safest landing technique, wing loading plays a significant role in the type and severity of injuries sustained. The ISI for these incidents was 2.16, and the severity of injury was strongly correlated to wing loading. On average, those who loaded their canopies below 1.05:1 sustained injuries such as minor cuts and bruises or a single broken bone. As wing loadings increased above 1.05:1, the severity of injuries drastically increased. All jumpers should practice and become proficient at canopy skills before downsizing to smaller canopies where the consequences of mistakes become much more costly.

To find out more common causes of landing injuries to jumpers, we broke down the non-turn-related incidents into further subcategories:

- Obstacle: Hit an obstacle

- Pattern: Performed a poor landing pattern

- Turbulence: Encountered turbulence, and it was the primary cause of the injury

- Flare/PLF: Flared and/or performed a parachute landing fall poorly or not at all

- Tandem Student: These reports specifically stated that the student didn’t keep their legs up for landing

- Other: The report did not include enough information to categorize properly

For the fourth year in a row, the Flare/PLF category accounted for the highest percentage of non-turn-related incidents. In most cases, the failure to flare or PLF, not the poor performance of either, was the cause of injury. Thirty percent of these incidents were after the jumper had performed a poor pattern, possibly due to the increased stress levels that manifest in the final stages of landing. A good landing starts at 1,000 feet, and a good stress-free pattern seems to allow a jumper to perform better in the final stages.

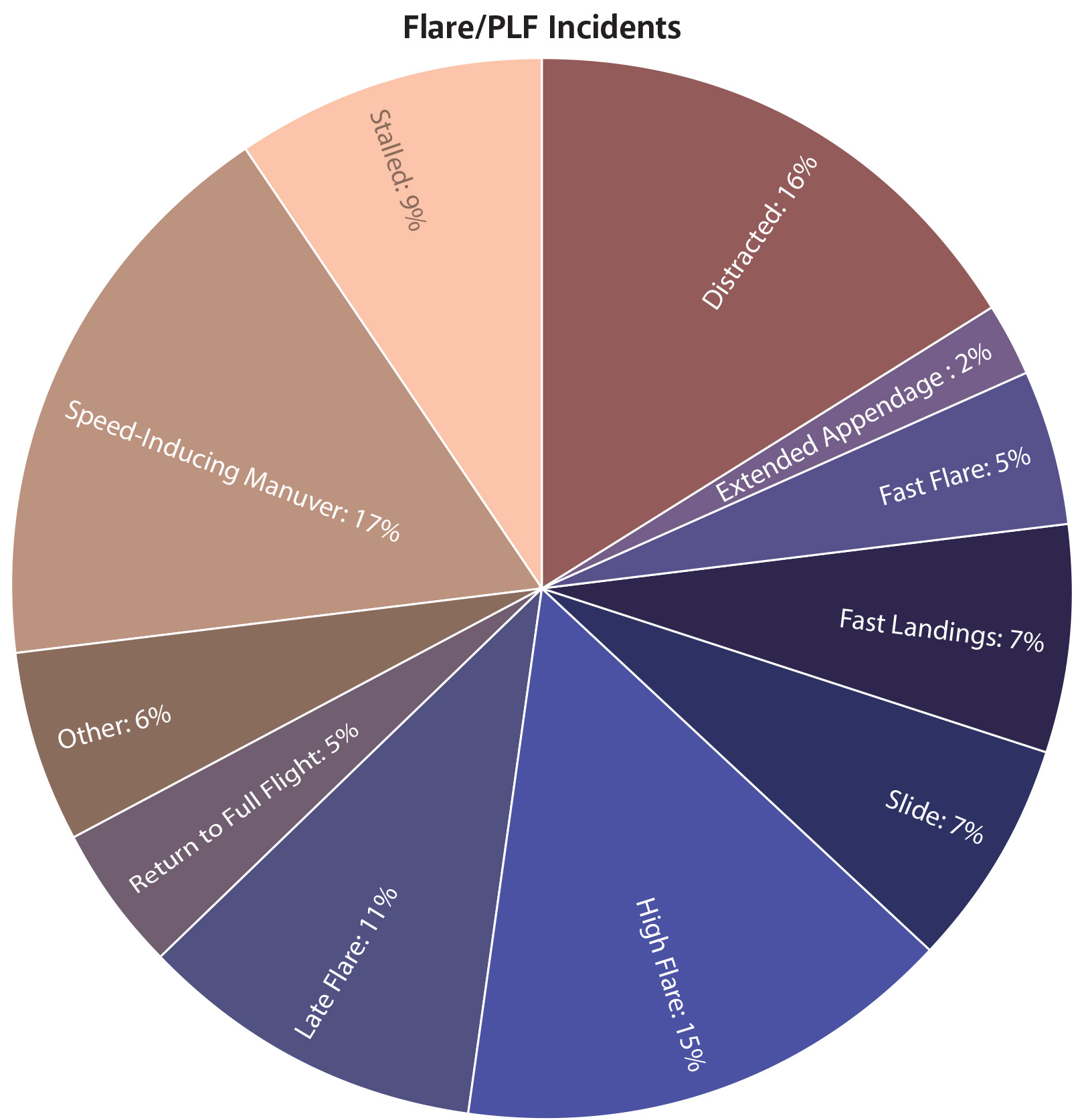

This year, we dove a little deeper into the Flare/PLF category, resulting in 11 subcategories of causality.

- Distracted

- Extended Appendage

- Fast Flare: Flared Too Quickly

- Fast Landings

- High Flare

- Late Flare

- Return to Full Flight after Flaring Too High

- Slide

- Speed-Inducing Maneuver

- Stalled

- Other (not enough information to correctly identify)

Interestingly, the largest contributing factor to this category is flaring too high (20%): comprised of 1) return to full flight after flaring too high (5%) and 2) high flare (15%). The average ISI was 2.2. Students represented 54% of the overall high-flare incidents and 75% of the returned-to-full-flight category. On the other hand, students also were prone to flare too late. With an ISI of 1.8 (0.4 below flaring too high), this seems to be the less costly mistake. SIM Section 4-A.D.7.f says, “If you start the flare too high, stop flaring and hold the toggles where they are. … Push the toggles the rest of the way down before touching down.”

Also interesting is that the second largest subcategory was a poor flare or PLF following a speed-inducing maneuver. D license holders dominated this subcategory at 53%. The average ISI was 2.5, tied with the ISI rating for jumpers who stalled their canopies during the flare, making these two subcategories the highest in the flare/PLF category. When jumpers start experimenting with speed-inducing maneuvers, the added speed can be startling and cause delayed reactions. They may also be using poor flare techniques. This is why it is so important for jumpers to practice these maneuvers higher until they can adjust and improve.

Students and A license holders dominated the third largest subcategory, distracted landings, at 64%. These incidents included obstacles on the ground, canopy traffic, ground grade (either landing uphill or downhill) or turbulence distracting the jumpers. It appears that less-experienced jumpers are more prone to distractions during landing. Although jumpers need to use their peripheral vision to stay situationally aware of their surroundings, jumpers must focus more on their landings the closer they are to the ground.

The fast-landings subcategory is comprised of jumpers who attempted to run out their landings and the slide-in subcategory included jumpers who tried to slide in a landing but hit uneven ground, a hole or a clump of grass. In either case, they were moving too quickly to land safely using their attempted method and would likely have fared better had they performed a PLF. In most cases, these jumpers broke an ankle or wrist in the process. With no reports of injuries sustained during PLFs, presumably the jumpers who chose this method fared better.

Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 4-A gives great advice: “You should be prepared to perform a parachute landing fall every time you land,” and follows that up with, “A stand-up landing should be attempted if you touch down softly and are confident that you can comfortably remain on your feet.” Farther down the section, it says, “Anytime you must land in an alternate landing area off the airport property, perform a parachute landing fall.” The PLF is a necessary tool that every skydiver should rehearse periodically to stay proficient.

Next Month: The 2022 Non-Fatal Incident Summary—Part Two