Part one of this article (June 2024 Parachutist) provided an analysis of the 114 landing-incident reports in 2023, which made up 48.1% of all non-fatal incident reports for the year. Here in part two, we look at the remaining 123 reports, all concerning incidents that did not occur during landing. To identify specific issues and develop recommendations for the most significant areas of concern, we’ll focus on the two largest categories: equipment problems and incorrect emergency procedures.

Incident Rate (IR): The number of incidents per 1,000 jumpers in a license category

Equipment Problem: 39, 16.46% (2019-2022–7.5%)

This year, the precentage of incidents in the equipment-problem category increased 9% over previous years, a concerning statistic that may indicate that jumpers are neglecting to perform manufacturer-recommended maintenance or are using equipment past the recommended service life. When looking at the license levels of jumpers affected by these incidents, the highest percentage are D-licensed. However, there are far more D-licensed jumpers than students, and a closer look shows that the incident rate—the number of incidents per 1,000 jumpers at that license level—shows that students are twice as likely than licensed jumpers to have an equipment problem .

The common causes of equipment problems are reflected in the following subcategories. These subcategories reveal the causes of equipment problems in 2023:

- AAD Fires

- Drogue/Bridle

- Gear Checks

- Gear Maintenance

- Gear Rigging

- Jumper Performance

- Packing

- Spinning Line Twists

- Toggle Fire

Gear Maintenance (31% of Equipment Problems)

Line issues—including tension knots, line twists (several spinning) and a knot around a guide ring from pulling the toggle through the line excess—accounted for 59% of maintenance incidents. Fortunately, most of the jumpers either resolved the issue above their decision altitude or performed emergency procedures and landed safely. Improper maintenance (of Velcro, a bottom-of-container pilot-chute pocket or a rapide link on a tandem container) was the other main complication reported in the gear-maintenance category.

In one notable incident, a jumper noticed a broken line on their 75-square-foot canopy that they loaded at 2.47:1. The jumper chose to perform their standard high-performance landing despite the malfunction. During the plane-out phase of the landing, as the jumper transitioned to rear risers, their canopy collapsed. First responders stated they believed the jumper broke a femur and dislocated an arm. Jumpers who opt to land a malfunctioning canopy should refrain from performing aggressive maneuvers during the rest of their canopy flight.

Jumpers should refer to their owner’s manuals to learn their gear’s inspection procedures and intervals. In areas where environmental conditions can speed up line wear, they must inspect their lines more often. Worn lines increase the odds that a jumper will experience tension knots or broken lines. More detailed information and line-inspection recommendations are available in the article “Know Your Lines” in the October 2020 issue of Parachutist.

Gear Checks (15% of Equipment Problems)

Every year, simple gear checks could have prevented many of the skydiving incidents that occurred. These include incidents such as premature deployment of the main or reserve, which can cause damage to aircraft along with being hazardous to other jumpers. This year, gear checks could have caught automatic activation devices that were off or improperly set, misrouted bridles that led to pilot chutes in tow and a wingsuit flyer who forgot to fasten their leg straps.

Over the years, skydivers’ vigilance in checking not only their own gear but also that of others has prevented numerous accidents and undoubtedly saved lives. Even experienced skydivers can get rushed and miss something, but the odds of two experienced skydivers missing the exact same thing on the same jump are highly unlikely. That’s why the USPA Board of Directors is adding terminology to Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 5-4: in 2025 that says:

a. Additionally, it is highly recommended that every jumper, regardless of experience level, engages in a mutual gear check with another licensed jumper. This peer-review process is an essential safety-verification step to identify and rectify any oversights or errors in equipment preparation.

b. The practice of mutual gear checks cultivates a culture of collective responsibility and vigilance, enhancing safety standards in skydiving activities.

Gear Rigging (13% of Equipment Problems)

These incidents included an improperly installed removable deployment system (RDS), incorrect cutaway-cable installation, misrouted brake lines that bypassed the guide rings on the risers and improperly installed soft links (Slinks). Except in the case of the soft links, the jumpers were able to manage the complications effectively and landed with minimal or no injuries. The jumper who incorrectly installed the soft links initiated a flare for landing using their rear risers, and a soft link failed, releasing all C and D lines on one side of the canopy. This induced a sharp turn just before landing and caused the jumper to land hard, resulting in several leg fractures. Just as it is wise to get a buddy gear check, jumpers should ask someone to inspect any newly added or reinstalled gear, particularly components that are not easily visible during a standard gear check.

AAD Fires (13% of Equipment Problems)

One incident in this category occurred when jumpers could not exit the aircraft due to a low cloud layer and the pilot descended rapidly, dropping below the automatic activation device’s firing altitude at a speed that caused activation. Jumpers must be familiar with their devices’ activation parameters and communicate these to pilots during descents.

Another incident involved a jumper who cut away from a malfunction at an altitude low enough that their AAD activated during the reserve deployment, suggesting a loss of altitude awareness. An AAD activation is a significant event that signals a departure from standard safety procedures (usually a loss of altitude awareness) and should be taken seriously. Any jumper who experiences an AAD activation should review the incident, identify their points of failure or substandard performance and view it as an essential learning experience to enhance their skydiving safety and skills.

Packing (10% of Equipment Problems)

A wide variety of packing errors, from jumpers packing step-throughs to neglecting to cock their pilot chutes, made up this category. Packing a parachute is an often-undervalued but critical skill. While many rely on professional packers, understanding how to spot a poor pack job is crucial, even for those who do not plan to pack themselves regularly. By learning the basics and practicing them, skydivers can enhance their safety.

Common packing mistakes include improper handling of the pilot chute, slider, brake lines and stow bands. These errors, although often manageable, can occasionally lead to severe consequences. Overpacking, incorrect slider placement and over-rolling the tail can also lead to problematic deployments. It’s also essential to understand how factors such as weather, body position and equipment interaction affect parachute performance. Skydivers should engage with the packing process, maintain a proactive approach to learning and follow proper packing techniques.

Jumper Performance (8% of Equipment Problems)

These incidents primarily involved students but included one A-licensed jumper who snagged their pilot chute on the trim wheel of a Cessna 182 as they climbed out of the aircraft. Luckily, a jumper outside on the step noticed and pushed the jumper off the plane before the parachute could deploy, potentially saving the jumper and the aircraft severe damage. Jumpers must protect their handles when moving around an aircraft and verify they are still in place before approaching or exiting the aircraft door.

One of the student incidents involved a jumper on a 240-square-foot canopy loaded at 0.9:1 who made 360-degree turns down into their landing-pattern altitude, which caused the AAD to fire. Other incidents involved unstable deployments, which caused line twists. Some kicked out of the twists and others cut away, but all these jumpers landed without further incident.

Spinning Line Twists (7% of Equipment Problems)

Toggle fires (a steering toggle releasing prematurely) caused at least 62% of the spinning-line-twists incidents, with no cause reported for the remaining 38%. One of the reports indicated that excessive wear on the toggle keeper may have contributed to the toggle releasing during deployment.

Spinning malfunctions can lose altitude rapidly and require a quick resolution. In order to reduce fatalities in this category, USPA’s “Don’t Delay—Cut Away!” campaign in 2019 reminded jumpers to respond quickly to spinning malfunctions. Fortunately, these jumpers did just that: cut away at or above their decision altitudes and landed safely.

Incorrect Emergency Procedures: 18, 7.6% (2019-2022–7.5%)

Usually, less-experienced jumpers dominate the incorrect-emergency-procedures category. However, D-licensed jumpers comprise 25% of reported incidents in the category this year. This may indicate that D-license holders were once reluctant to report mistakes (possibly due to embarrassment) but are now recognizing the importance of reporting for improving safety.

Still, the incident rate—which accounts for the different population sizes within each license category—shows that students are still five times more likely to perform emergency procedures incorrectly compared to licensed jumpers.

This reinforces the need for instructors to provide thorough and effective training and plenty of emergency-procedures practice before student jumps.

Although jumper proficiency generally increases with experience, the incident-rate-adjusted data shows a gradual increase in the incident percentage from B- to D-licensed jumpers. This suggests that jumpers may require additional practice post-B license to maintain their proficiency and highlights the need for continuous training for intermediate to advanced skydivers.

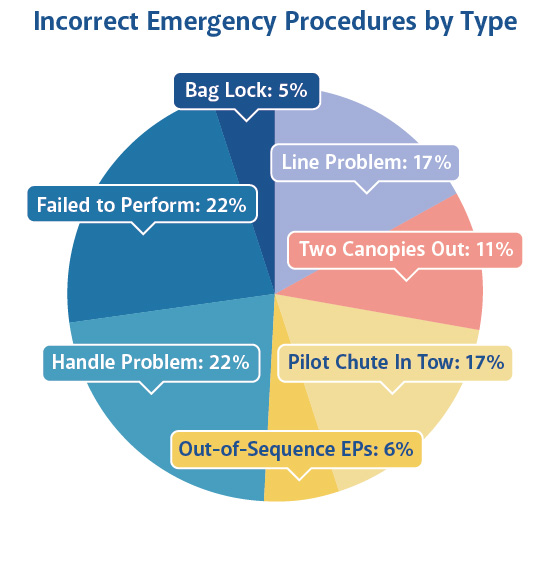

To focus more precisely on causes and possible solutions, the incorrect-emergency procedures category is divided into subcategories. This article focuses on incidents that account for more than 10% of incidents within the category.

Failed to Perform (22% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

These incidents all involved students. Fifty percent did not perform emergency procedures under a canopy that was turning because one toggle was released and the other stowed. These jumpers spiraled to the ground and sustained serious injuries during landing (average ISI = 4). The other half experienced severe instability issues that continued until their AADs activated. All had good reserve deployments and sustained minor to moderate injuries (average ISI = 1.5) during landing.

In one instance, both instructors followed the student down until the AAD deployed the student’s reserve. They both then turned and deployed their main canopies, but their AADs activated their reserves, leading them both to have two canopies out at a low altitude. One instructor landed in a parking lot and sustained minor injuries. The other landed in a tree and was not injured. The student landed on a sidewalk after their canopy struck power lines, limping away with a severely sprained ankle, a possible concussion and some minor facial lacerations.

The incidents in this category highlight the importance of rigorous ground training, including freefall body positioning, altitude awareness and pull-priorities. It is equally important for instructors to preserve their own safety. Every report of students losing control and tumbling until AAD activation reveals that students managed to land safely due to the AAD deploying the reserve. However, instructors frequently endanger their own safety trying to assist. Instructors must maintain altitude awareness and adhere to safety protocols, ensuring they track away by 3,500 feet and deploy their main canopies by 2,500 feet.

Handle Problem (22% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

These incidents—where jumpers were unable to locate their main-deployment handles and lost altitude awareness—primarily involved student jumpers. However, one D-licensed jumper also experienced this problem. Fortunately, in all cases the AAD activated, and the jumpers landed safely. The predominant issue was improperly sized gear, which hindered the jumpers’ ability to access their main handles. Instructors must ensure that all equipment, not only the canopy but also the container and other accessories, are appropriately sized for each student. While most instructors diligently consult SIM section 5-3 for canopy sizing recommendations, they must give equal attention to the entire gear setup. Additionally, instructors need to account for the dynamic forces that freefall exerts on equipment, which can differ significantly from the conditions on the ground.

Pilot Chute in Tow (17% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

Pilot Chute in Tow (17% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

The pilot-chute-in-tow incidents stemmed either from errors packing unfamiliar equipment or maintenance issues, such as a bridle breaking at a connection point. In these cases, the jumper did not properly perform their emergency procedures at appropriate altitudes. These situations emphasize the importance of thorough training on new equipment and adhering to manufacturer-recommended inspections. Fortunately, the consequences were relatively mild, with the only reported injury being minor bumps and bruises resulting from an off-airport landing on a reserve parachute. This underscores the necessity for jumpers to be well acquainted with their gear and vigilant about its maintenance.

Line Problem (17% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

These non-fatal incidents involved jumpers who failed to perform a canopy-control check (CCC) after deployment and decided to land canopies while experiencing line-related malfunctions. For instance, a student jumper faced a line-over—a brake line over the nose of the canopy—and failed to recognize it, opting to land with the unidentified malfunction. Fortunately, due to the low wing loading of 0.64:1 on a 240-square-foot canopy, he landed safely, even without the ability to flare. In contrast, a B-licensed jumper encountered a more severe issue with a brake line entangling other suspension lines, leading to a canopy collapse during the flare, which resulted in the jumper breaking their pelvis.

The first-jump course teaches all jumpers the timing and procedure for performing a CCC. Unfortunately, after numerous jumps without incident, many jumpers become complacent, often foregoing this critical check after a superficial visual inspection of the canopy seems satisfactory. This neglect underscores the vital need for consistent adherence to safety protocols such as the CCC, regardless of past outcomes, to prevent such avoidable accidents. A fatality occurs due to a jumper failing to conduct a CCC about every two years, and the last one occurred in 2023.

Two Canopies Out (11% of Incorrect Emergency Procedures)

This year, all of the reported two-canopies-out incidents in the incorrect-emergency-procedures category involved students. In each incident, the student had a main and reserve canopy flying in a stable, side-by-side configuration and cut away their main without first disconnecting their reserve static line and experienced an entanglement. Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 5-1 advises skydivers to first disconnect the RSL in all two-canopy-out scenarios since RSLs pose a significant snag hazard if there is a need to cut away the main canopy. These incidents highlight the need for thorough emergency procedures and equipment-management training for complex situations.

Based on the 2022 USPA Member Survey, a reportable incident occurs approximately every 570 jumps. If 100% were reported, USPA would receive 6,200 reports annually. Currently, we receive reports for approximately 5% of incidents—a significant increase from the 0.4% reporting rate in 2018, but still far from ideal. Please report non-fatal incidents and actively participate in USPA’s efforts to move closer to achieving a year with zero fatalities.

Any USPA member can file an incident report. You can find more information in the Skydiver’s Information Manual Section 5-8. An easy-to-fill-out, mobile-friendly online report form is available at uspa.org/ir.