Decades before the first person leapt from an airplane, fell through the air and pulled a ripcord, hundreds of parachutists had already made thousands of successful jumps. These early descents served no practical scientific, military or safety purpose; nor were they made for sport. The parachutists who made them were performers who cut loose from “smoke balloons” (balloons without onboard fire, propelled aloft after being filled with smoke from fires on the ground) for the entertainment of crowds at resorts, fetes and fairs. From 1887 through to World War I (and beyond, in a few places) there was a balloon-parachuting craze that appeared to have more in common with circus aerial acts than as a serious adjunct to aeronautical progress. Yet it was from the ranks of these spangled, tights-wearing daredevils that came forth many airship builders and early-bird pilots, as well as those who helped design the modern parachute pack.

It was on January 27, 1887, that a former circus tightrope walker, Thomas S. Baldwin, stepped out of the basket of a tethered balloon operated by Park A.Van Tassel and jumped from 1,000 feet above San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Baldwin was by no means the first person to parachute from a balloon; that had been done as early as 1797 by André-Jacques Garnerin. Throughout the early 19th century, other descents were made by Garnerin’s wife; his niece, Elisa Garnerin; Louis Charles Guillé; John Hampton; Eugene and Louise Poitevin; and Eugène and Auguste Godard. The parachutes used by these jumpers were semi-rigid, i.e., fabric stretched over a light framework. In some cases, the ascent was made with the parachute already extended in an open position; in all cases the parachutists stood in a small car (basket) suspended underneath the parachute and remained there during their descent.

Tom Baldwin’s jump came many years after those mentioned above, but the crucial difference was his frameless, all-fabric parachute. Audiences could plainly observe Baldwin jumping from his perch and falling rapidly for 100-300 feet before air filled his parachute. Baldwin descended by hanging by his hands from an iron ring, his legs dangling and his whole body in view. In the decade prior to Baldwin’s leap, several daredevils (including Baldwin) had thrilled crowds by hanging from a trapeze bar under a balloon in place of a basket; Tom Baldwin took that act to its next progression. A bright aerialist outfit not only accentuated his physique but made it easier to spot his figure in the sky.

Baldwin and Van Tassel later both claimed to have come up with the idea of the all-fabric parachute, but the truth is that they obtained a working design from acrobat Charles Leroux (real name Joseph Johnson), who happened to be in San Francisco in January 1887. In the previous year, Leroux had given several demonstrations of jumping from buildings and bridges with a parachute he designed but had never jumped from a balloon. If Baldwin and Van Tassel modified Leroux’s design at all, it was likely that they increased the diameter after making some test drops in a large concert hall.

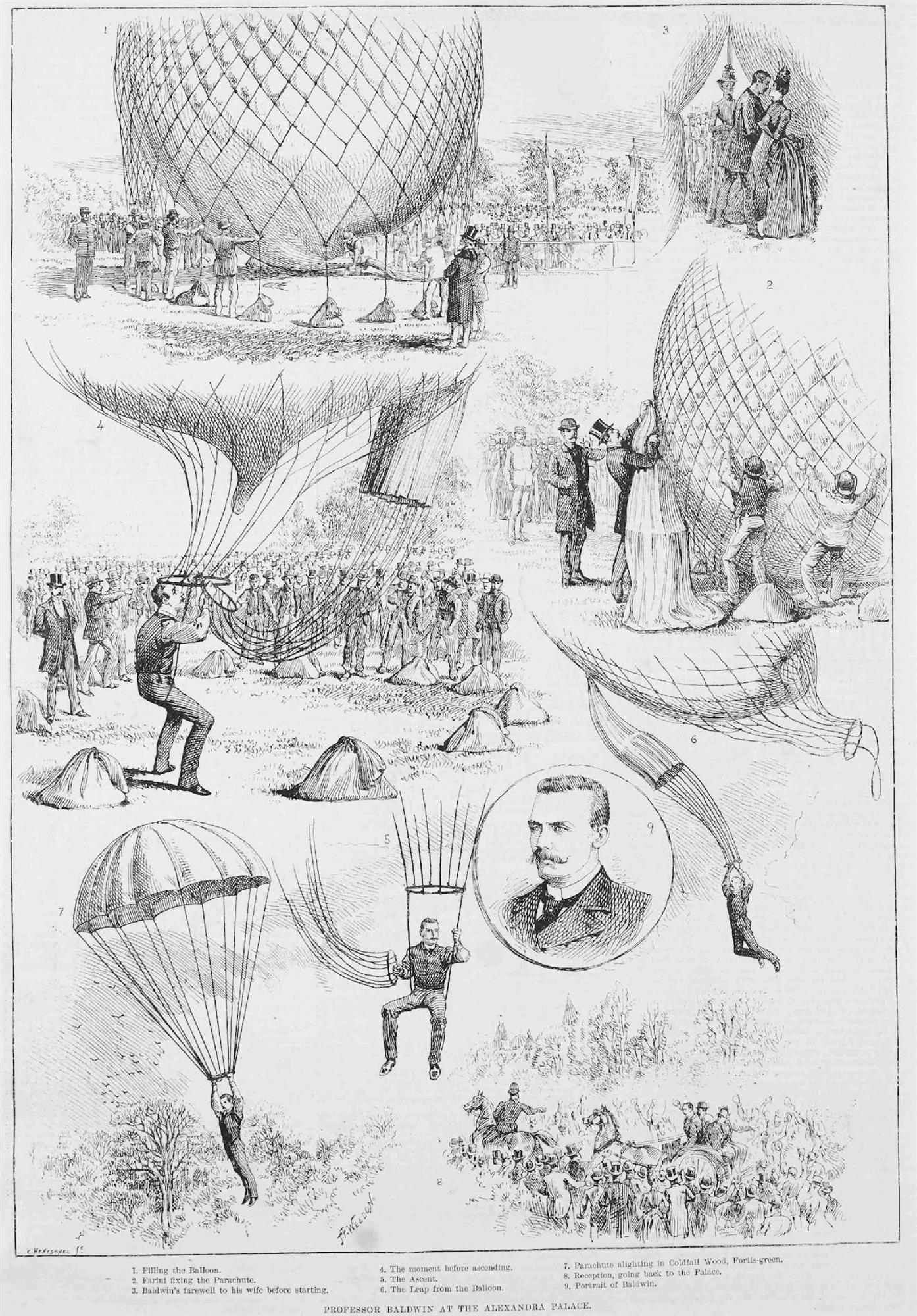

Illustrations of Tom Baldwin performing at the Alexandra Palace in London appeared in the Illustrated London News on September 19, 1888.

Illustrations of Tom Baldwin performing at the Alexandra Palace in London appeared in the Illustrated London News on September 19, 1888.Though Baldwin’s performance in California was widely reported, other show balloonists did not take notice until Baldwin came farther east and made another descent on July 4, 1887, in his hometown of Quincy, Illinois. As a result, the whole city of Quincy was engulfed in a parachuting craze, led by Tom Baldwin and his brother Sam. Other show balloonists suddenly took note, and before 1887 ended, Baldwin had nearly a dozen imitators—though several used a design in which they were suspended by the parachute lines during the whole ascent and used a rope connected to a blade to cut the chute free from the balloon. The result was far less dramatic than Baldwin’s configuration of the parachute suspended from the side of the balloon, which separated via a breakaway string after he jumped.

Baldwin’s first appearances netted him at least $1,000 per jump. The first jumpers to follow Baldwin reaped some of those benefits and were led by veterans from a handful of show-ballooning hotbeds: Jackson, Michigan; Quincy, Illinois; Springfield, Illinois; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Cleveland, Ohio. Within 10 years, parachutists were recruited off the street with no training, making jumps for $10 or $20. Fair and resort managers contracted with ballooning outfits that offered the cheapest price, and with no regulation, safety and good equipment were rare commodities. Between 1888 and 1910, more than 100 balloon-parachutists were killed, and many more were maimed. In 1895, The Boston Post estimated that the average career span of a parachutist was two years before they suffered a life-ending accident.

Lack of training, poor equipment and lax safety measures caused only a portion of the accidents. Other dangers included: latent sparks from the inflation furnace causing the balloon envelope to catch fire (made more likely if winds during inflation moved the balloon fabric closer to the flue), overinflation causing the balloon to burst as it rocketed to an altitude with lower air pressure and having the loosened balloon collapse and drop right on top of the parachute while descending.

For those who might think that jumping from a balloon with little freefall was sedate, consider the ascent of smoke balloons. These bags were often overinflated on purpose, with the intent of rocketing the jumper to 1,000-3,000 feet as quickly as possible, without drifting far from the launch point. This was done to give spectators the best view and to have the unpiloted balloon collapse and land where it could be easily retrieved. Veteran scientific balloonist Carl Myers (who also reluctantly operated as a show balloonist to generate money for his pursuits) did not like to call these “balloons” at all—he described them as “projectiles.” Looking for a thrill? Try being launched by a smoke balloon while sitting on a rope swing!

Although smoke-balloon aeronauts experienced a few seconds of freefall before air filled their chutes, none described it as exhilarating. In fact, most thought that it was terrifying, since the prevalent belief—which persisted for many years into the 20th century—was that an extended freefall was deadly: that the body either died from shock or had air sucked from the lungs long before the impact of hitting the ground.

Ascents were made even riskier by winds that could dash the aeronaut against trees, buildings, telegraph lines and towers, which the parachutist was helpless to avoid, since they did not have enough altitude to make a jump. The same obstacles could be encountered upon descent, though these early parachutists quickly learned that tugs on the parachute lines gave them at least some maneuverability. They also soon learned the correct way to fall on landing. Many preferred to land in soft, newly plowed fields. Some even preferred water landings, though being caught in lines and dragged underwater was the cause of several fatalities.

As Tom Baldwin’s disciples spread across the United States, Baldwin himself started a global tour in 1888, beginning in London, England—the era’s foremost cultural capital. His performances at the Alexandra Palace grounds proved every bit as popular as the previous season’s appearance in London of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows. From Great Britain, Baldwin continued his tour to make stops in Europe, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. However, by the time he reached the Antipodes, Baldwin discovered that he had already been eclipsed by his imitators. With his profits dwindling, Baldwin reversed course, returned to England and then set sail for New York.

Among those who brought the balloon-parachute act to East Asia were Baldwin’s old partner, Park Van Tassel, accompanied by another Illinois show balloonist, James Price. Van Tassell and Price spent nearly the entire decade of the 1890s touring Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Asia and South Africa, though they had parted ways after just one season. Van Tassel’s tours of Asia and his performances before kings, emperors and rajahs, employing a series of young women aeronauts, is likely one of the great untold romantic epics of orientalism.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the balloon-parachute act became a staple act for county and state fairs, holiday fetes and summer resorts. For the most part, the first generation of independent balloon-parachutists gave way to touring companies: the Baldwin Brothers (led by Tom Baldwin’s brother Sam), the Grace Shannon Balloon Company, the Leroy Sisters, the Jewell Brothers, the Flying Allens, the Forsman Balloon Company, the Hepner Brothers Balloon Company and the Belmont Sisters. Among the most noteworthy of these companies was the New York Balloon Company, which for several years made its headquarters at the Eldorado resort on the Weehawken palisades overlooking Manhattan.

The New York Balloon Company’s collection of merrymaking aeronauts was led by A. Leo Stevens, a born daredevil and a former tightrope-walking prodigy. Stevens encouraged his pals—male and female—to engage in extracurricular (and illegal) parachuting from New York’s landmark bridges. On one occasion, in 1897, Stevens supplied his friend Charles Lastrange with “parachute wings” that carried him 1,000 feet downriver in his jump from the Brooklyn Bridge. Similarly, aviation pioneer pilot Bud Mars had toured as a balloon-parachutist in 1903, and employed a paragliding parachute he called the “Fool Killer.” No design details or pictures survive of either of these devices.

Over the years, new wrinkles were added to the balloon-parachute act: parachuting pets; sham races between parachutists dropping from separate balloons; double-drops from separate sides of a single balloon; double-drops of parachutists in which one was suspended beneath the other; one parachutist deploying multiple parachutes in one drop; parachutists that descended astride a bicycle; balloons with a cannon suspended underneath it that shot out a human cannonball with a parachute; and the penultimate act, a parachutist who emerged from within a giant exploding pyrotechnic bomb shell. The last-mentioned stunt was pioneered by none other than A. Leo Stevens, with an assist from Pain’s Fireworks.

Käthe Paulus demonstrates the technique for parachuting off a balloon in this studio portrait.

Käthe Paulus demonstrates the technique for parachuting off a balloon in this studio portrait.Ironically, the fake-cannon act may have played a part in the progress toward a practical parachute pack, for this stunt required the parachutist to lay in a hollow cylinder with his parachute folded above his head. When the cannon was “fired,” a loud smoke bomb was set off, and the cylinder lowered at one end to let the parachutist drop out, the chute trailing him. This was the mechanism that likely inspired the first person to parachute from an airplane, Bertram B. Berry. In March 1912, Berry fitted a metal cone in which a parachute was folded to the undercarriage of an airplane. With Tony Jannus piloting the Benoist aircraft, Berry crouched in the undercarriage until they were high over the Jefferson Army Barracks and then jumped. He fell freely for 500 feet before the parachute opened, landing successfully. Because this jump was made over an army base, the little-known Bert Berry has often been cited as “Capt. Albert Berry,” but in truth he was an ex-con with a troubled background and disappeared into obscurity just a year after his claim to fame.

Berry was hardly the only person to contribute to the parachute pack. In 1910, Katharina Paulus, Germany’s most famous balloon-parachute performer, devised a parachute pack that used a breakaway cord to separate the parachute from the pack attached to her balloon. At about the same time, Russian actor Gleb Kotelnikov was motivated to invention by a tragedy. Kotelinikov witnessed the death of Captain Leo Matsievich during an air show in 1910. He devised a backpack for the parachute, opened via a static cord attached to the plane or manually by the wearer.

Leo Stevens publicly announced that he was working on a parachute-pack project in 1911, and soon found a willing subject to test his ideas. Frederick Rodman Law, an idle steeplejack, claimed that he approached Stevens looking for a parachute to pull off a high-dive stunt for photographers and movie cameramen. The tower that Law chose to make his jump from was the raised torch arm of the Statue of Liberty—though it is equally plausible that the idea originated with the prankster Stevens. On February 3, 1912, Stevens and Law went to Liberty Island and presented an authorization paper from the War Department that Stevens had conjured. They proceeded to the top of the statue and went up inside the arm, emerging at the balcony around the torch. The wind was blowing a stiff 20 m.p.h. The New York Daily Star described the scene: “’It looks a little risky, Fred,’ remarked Stevens, peering over the edge of the torch rim to the base of the statue, 200 feet below.” F. Rodman Law took a puff from Stevens’s cigar, and then jumped off Lady Liberty’s balcony. A tethered line pulled the ripcord of the prototype parachute pack, and Law drifted safely to the ground. The result was headlines in newspapers around the world. Later in 1912 (after Bert Berry’s airplane jump), Leo Stevens coached several men in making tethered jumps from planes using his parachute pack.

In 1908, an itinerant balloon-parachute performer, Charles Broadwick (real name John Henry Murray) introduced double and triple parachute jumps made by his partner, Georgia “Tiny Broadwick” Thompson. The Broadwicks moved to Southern California, where a new teenaged assistant, Leslie Leroy Irvin, was hired to make balloon jumps. On January 23, 1912, Tiny Broadwick performed at Dominguez Field in Los Angeles during the International Air Meet, her act sandwiched between airplane demonstrations by many of the greatest airmen of that era. Aircraft builder Glenn Martin was deeply impressed by her double parachute jump and wondered if the packing of the second parachute could be adapted for use in making a leap from an airplane. Martin approached Charles Broadwick to help develop a “coatpack” mechanism using a static line to the airplane. In June 1913, Tiny Broadwick made a public demonstration of the device by jumping from Martin’s plane over Griffith Park in Los Angeles. The next season, Leslie Irvin took her place and made his first jump from an airplane. That same year, 1914, Glenn Martin applied for a patent of his “Martin’s Life-Vest,” leaving Broadwick’s role virtually forgotten. She is now best known as the first person to freefall, when in 1914—after her static line got fouled—she cut it short and made her next jump by pulling the parachute out manually.

Pilot Tony Jannus and Bert Berry with the Benoist-built biplane they used when Berry became the first person to parachute from an airplane on March 1, 1912. Courtesy of Missouri History Museum.

The onset of World War I, with a host of countries rushing military aircraft and spotter balloons into service, should have sparked a new round of development of the parachute pack. However, airplane pilots distrusted them, believing that releasing the plane’s controls to make a jump was dangerous, and military commanders believed that parachutes might cause pilots to ditch costly craft that might be able to land and be repaired. Consequently, little use was made of parachutes until the closing months of the war, and little had been done by the Allies to improve their design. Even so, by the end of the war, the U. S. Army recognized that a more efficient, reliable parachute pack needed to be developed, especially since aircraft had recently been built that could carry a crew—or troops.

At Dayton’s McCook field, Major Edward L. Hoffman gathered a panel to review existing parachute pack features. The board included Floyd Smith, a former acrobat and mechanic for Glenn Martin; Guy Ball, another California mechanic; and Harry Eibe, a balloon-parachutist from Greenville, Ohio, close to Dayton; Sgt. Ralph Bottreil, an experienced jumper; and engineers James J..Higgins and James M. Russell. Hoffman’s team examined all existing parachute pack features, including those used by the Broadwicks; Leo Stevens Safety Pack; the German Otto Heinicke; Floyd Smith’s modifications to the Broadwick/Martin pack; and, similarly, the modifications that Leslie Irvin made to the Broadwick pack he had used. Hoffman’s panel arrived at a combination of the best features of each and identified it as the “U.S. Army Air Service Type A Parachute.” This pack served as the foundation for the modern parachute pack and gave rise to skydiving as a sport.

Although no longer presented as an entertainment for crowds gathered below, sport skydivers still regularly parachute from balloons. USPA requires a B license or higher to make a balloon jump; skydiving into dead air heightens the sense of freefall, and, combined with the relative lack of noise, makes it a unique experience. High-altitude-record setters such as Joseph Kittinger, Yegeni Andreyev, Felix Baumgartner and Alan Eustace made their jumps from helium balloons. Baumgartner’s record-setting jump in 2012 (bested by Eustace two years later) was accompanied by a great deal of hype and publicity, and the global audience watching would have been the envy of Tom Baldwin and his imitators.

About the Author

About the Author

Jerry Kuntz is a historical researcher and writer residing in the Hudson Valley, New York. McFarland Publishers will publish his book “A Leap from the Clouds: The Balloon-Parachute Act and the Daredevil Heritage of Aviation” in June 2022.