Part Two: Tandem and Beyond

These days, with millions of tandem skydives safely completed around the globe each year, it’s hard to imagine skydiving without it. In the 1980s, about the same time the accelerated freefall program was in development (see part one of “You People Did What?!—The Long and Sometimes Crazy History of Skydiving Instructional Methods,” January Parachutist), this new type of student training was in the works. The path toward tandem skydiving was a long and crooked one and had some potholes, to boot!

Tandem Skydiving

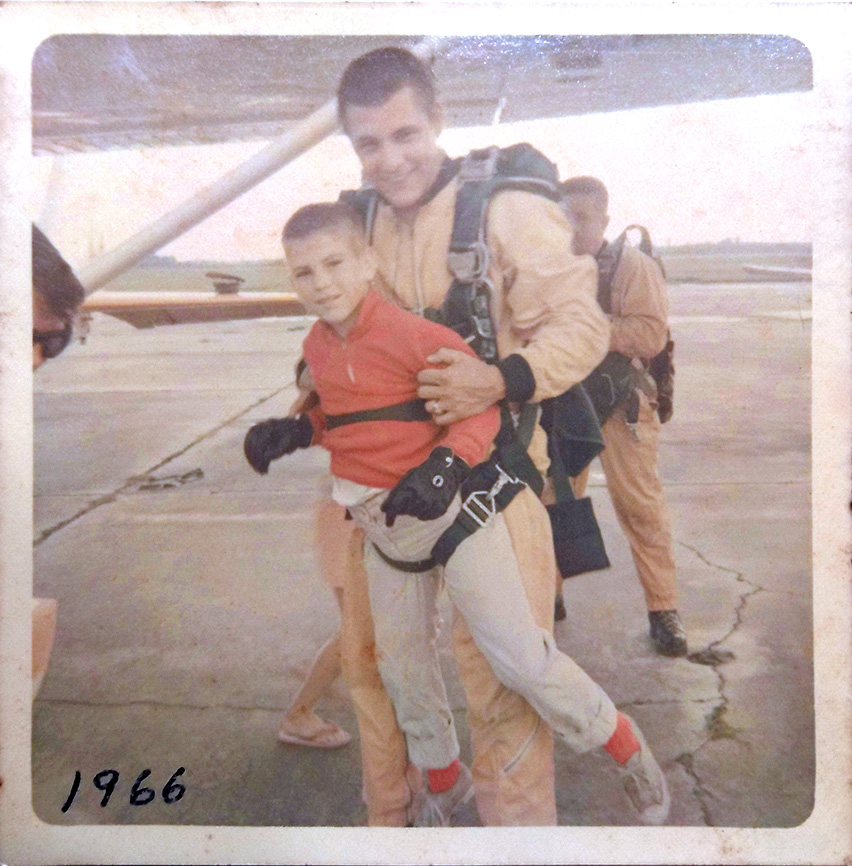

In the 1960s, some trailblazing people made attempts at dual-jumper skydives, but the equipment of the day was a limiting factor. T.K. Donle, who managed the early tandem program for Bill Booth’s Uninsured Relative Workshop (now United Parachute Technologies, maker of the Sigma tandem system), recalled the early days that got him interested in tandem skydiving: “Dupy [Gary Dupuis] made the first tandem jump in DeLand [Florida] in 1966 with a 10-year-old boy. The second tandem jump was made by Gary’s older brother, Joe Dupuis, who jumped with their younger brother, Roger Dupuis. He was also 10 years old and nicknamed ‘Ace;’ he went on to be a U.S. Army Golden Knight.

Gary Dupuis gets ready to take a 10-year-old boy up on the first-known tandem-style skydive.

Gary Dupuis gets ready to take a 10-year-old boy up on the first-known tandem-style skydive.“The rig they used [for that first jump] was an early model Security piggyback with a 24-foot Para-Commander and a 26-foot lopo reserve. Gary built some special harnessing to attach his small passenger to his rig. The boy’s legs went into the same leg straps Gary used. Then a separate chest strap and belly band were added to keep the kid securely attached. His goal was to make the first parachute jump safer for first-time jumpers. But he soon realized that the landings were challenging, and he really could not jump with adult-size passengers; the canopies were the limiting factor.”

Donle continued, “About six years later, in 1972, Booth made a tandem jump with Stan Carter in South Florida at the Homestead Glider Port. They used an old military surplus cargo chute about 44 feet in diameter. They somehow rigged the canopy’s risers to their chest straps. Like Dupy six years earlier, Bill wished there was a better way to introduce students to their first jump other than static line. He too realized that more advancements in equipment needed to take place before tandem with two adults could be safely done.”

The idea that eventually spurred further development of tandem skydiving came from a sketchy skydive that took place in Florida in 1975. Gloria Chace wanted to jump a square parachute, but her husband, Pete Chace, D-61, didn’t want her to since she was only a novice with 10 jumps under her belt, all under round parachutes. So, he decided he would take her up for a jump while strapped into his harness. He had recently performed this stunt twice with Gypsy McKeehan, and Gloria was jealous (about the skydive, not that her husband was jumping with a pretty, young girl!).

Gloria and Pete Chace climbed into a Cessna 206 and ascended to 15,000 feet over a cloud-filled sky near Jupiter, Florida. On the way up, Pete cut a seat belt out of the 206 to use as a chest-strap extender, and Gloria stuck her legs through his leg straps. Pete deployed the main right away, but the sub-terminal deployment was still extremely hard. The pair descended through the sky with only a compass to help them navigate through the clouds. They landed in a soybean field with a head-over-heels tumbling crash under the 180-square-foot Stratostar five-cell main canopy. Gloria initially thought she broke her leg on landing but otherwise, the jump under the square was all she had hoped for! She loved it but decided one jump was enough.

Soon after the jump, Gloria Chace excitedly recounted the details to her friend Bill Morrissey, D-516. He had heard about other skydivers taking their kids up in the same fashion. Morrissey was struck by her excitement and thought that there might be something to this dual-jumper stuff. But life got in the way, and it was another seven years before Morrissey headed back to Florida to see his old friend Ted Strong to discuss the idea of a dual-jumper harness system. Strong was the owner of Strong Parachutes Inc., and his facility could build the necessary equipment.

The pair met for lunch in July 1982 at a Chi-Chi’s restaurant in Orlando, Florida. By the end of the lunchtime discussion, Strong had sketched out the initial design of a dual-harness tandem system on the back of a placemat. They hugged at the end of the meeting, excited by the idea that this new training method would attach an experienced instructor to each student. They both thought it would be the end of student fatalities. Unfortunately, history would prove that not to be the case.

Ted Strong (left) and Bill Booth (right) make a pre-drogue “two by four” skydive together. Photo by Norman Kent.

During the first half of 1983, Strong made a few test jumps with his employees using some equipment he developed at his factory. From those test jumps he quickly realized that this new form of student training would require both specialized equipment and specialized training. In July 1983, he shared his experiences with Booth, the owner of the Relative Workshop, who was also developing a tandem parachute system. (Morrissey later said, “Ted never could keep a secret!”)

In September 1983, Strong and Booth made a tandem jump together, which Strong called a “two by four.” The two tandem pairs docked in freefall, each using their latest tandem equipment. All the testing and jumping up to this point did not include the use of a drogue parachute. Freefall speeds were fast, and the parachute openings were quite hard on most of the jumps.

Strong then hired Morrissey to help him develop this new tandem program. In October 1983, the pair made two tandem jumps, alternating who was on front. And with two tandem jumps under his belt, Morrissey became the world’s first tandem examiner … he just needed to figure out what to do from there!

Morrissey continued to make tandem jumps at large boogies, and he even travelled to Europe promoting the idea of tandem skydiving. But there were still two major hurdles to overcome:

- Tandem skydiving was a violation of the Federal Aviation Administration regulations for skydiving. At the time, all intentional skydives required each skydiver to use a single-harness, dual-parachute system. Tandem skydives used a dual-harness, dual-parachute system.

- The fast freefall speeds of tandem pairs combined with the deployment characteristics of early ram-air parachutes created brutally hard openings. Something had to be done to create a consistently soft opening for tandem jumps or this new training method would never get off the ground.

In November 1983, Morrissey attended the Turkey Meet in Zephyrhills, Florida, to demonstrate the new tandem system. This was a huge event with hundreds of skydivers in attendance, so it was a perfect place to expose them to this new concept. Morrissey made a tandem jump—his third—with Anibel Dow, a licensed jumper attending the meet. The parachute opened so hard that Dow injured his back and Morrissey landed bleeding heavily from his forehead. But they had bigger problems during the jump. All but two of the A lines broke during the deployment, and the canopy had heavy structural damage. Morrissey pulled the cutaway handle, but only one riser released. The RW-1 ring (the large ring on the 3-ring system) had elongated from the hard opening and would not release! Morrissey promised God that he would be a good boy if he could help him out a bit, and with that he pulled the reserve ripcord. The reserve opened cleanly and removed tension on the main riser, allowing for a cutaway. They landed in a cloud of dust and blood, sliding through the pea pit into a heap under the 270-square-foot reserve parachute. World famous record organizer and drop zone owner Roger Nelson stood over the pair and said, “Bill, you’re going to have to show me something better than that!”

To tame the hard openings, early tandem jumpers usually limited themselves to very short delays or took extra effort while packing the parachute to slow its inflation. Strong realized that neither of these strategies would work well as a long-term solution. By the time Morrissey returned from demonstrating tandem skydiving in Europe, Strong had adapted the system by adding a drogue parachute, which he was already using on equipment for smoke jumpers in the U.S. Forest Service. A static line deployed the drogue parachute, which the instructor released by pulling one of two ripcords that deployed the main parachute. Not only did the drogue slow down freefall speed and soften parachute openings but the ripcord was incorporated onto the student harness for training purposes.

Morrissey took the drogue-system tandem to Skydive DeLand in Florida and talked longtime jumper Jon Starke into making a tandem jump with him. On the same DC-3 airplane, Booth and several other jumpers were using his drogueless tandem system, making short delays. Morrissey hand-deployed the drogue on exit and allowed Starke to make turns and track during the droguefall. Upon landing, Starke was quick to tell everyone in the landing area how great the drogue was for tandem freefall. Booth had been reluctant to incorporate a drogue, calling it “a malfunction looking for a place to happen,” but within a few days of seeing Morrissey and Starke’s jump, he developed a drogue system for his tandem gear.

Early in the development of tandem, Booth, Morrissey and Strong met with attorney (and former Parachute Club of America President) J. Scott Hamilton to come up with the language necessary for a waiver from the FAA to allow tandem skydiving to be carried out under an exemption. It was also when Booth came up with the idea to call it “tandem skydiving,” comparing it to a tandem trailer system for trucking. By June of 1984, they received the waiver, expecting the FAA to change its rules to recognize tandem skydiving within the next two years. It took 18.

Ted Strong (left) and Bill Morrissey gear up to perform one of the early experimental tandem jumps.

Experienced skydiver Tee Taylor (student position) prepares to exit with Bill Morrissey while testing out the tandem system.

During this process, Morrissey decided on a 10-jump certification process for what were then called jumpmasters. Rating candidates made the first five jumps under the direct supervision of an examiner and then could make the second five jumps at their home drop zone. This allowed examiners to conduct the course on a weekend and keep the training economical for the candidate.

Initially, USPA was not involved with the certification of tandem jumpmasters. The Relative Workshop issued ratings for the Vector Tandem System and Strong Enterprises issued them for the Strong Tandem System. Under the FAA exemption, the tandem manufacturers had complete control over their tandem programs, including issuing and revoking ratings. USPA began to issue its USPA Tandem Instructor rating in 1996, but it still required USPA to verify that the tandem manufacturer had issued a rating. In June 2001, USPA received FAA approval for its own Tandem Instructor Rating Program, outlined in the USPA Instructional Rating Manual. That was also the year that the FAA updated CFR 105 to finally incorporate tandem skydiving. After 18 long years, the exemption was no longer necessary.

Tandem skydiving drastically changed the entire skydiving industry. Seeing the huge financial benefit of tandem skydiving, drop zones that offered only tandem skydiving began popping up across the country. Tandem skydiving exposed hundreds of thousands of people who would not otherwise have jumped to the sport.

Since the outset, tandem skydiving was popular across the U.S. and around the globe. Eventually more U.S. manufacturers built tandem systems, including Parachute Labs (Racer), Stunts Equipment (Eclipse) and Sunrise Rigging (Wings), as did several European manufacturers. In the early 2000s, Booth introduced the Sigma tandem system, which has taken over the tandem skydiving world as the dominant tandem system around the globe.

There is still room for improvement regarding tandem’s safety record. While Strong passed away in 2011, Booth is still active in skydiving and has been heavily involved in training, testing and manufacturing throughout the years. The industry has always worked to improve tandem system designs and moved quickly to address changes needed to prevent accidents, and its safety record is excellent. The challenge to improve tandem safety now lies largely with finding a way to eliminate human error.

The ISP and the Coach Rating

After several years of testing and development, on July 16, 2000, the USPA Board approved the Integrated Student Program—which introduced the USPA Coach Rating—as the association’s required student training program. The next day, Jim Crouch took over as director of safety and training at USPA Headquarters facing some big challenges. The ISP relied on coaches, who worked under the supervision of instructors, to perform much of the training and jumping in the latter half of the student progression. But the USPA Coach rating didn’t even exist, nor did the USPA Coach Rating Course, and drop zones were required to implement the ISP by January 1, 2001!

Fortunately, Director of Communications Kevin Gibson already had a course syllabus in the works, and he was fast at work creating course content. After first running a test course at Skydive Orange in Virginia, Crouch and Gibson traveled to Skydive Houston in Waller, Texas, to meet with local instructors, discuss the new program, answer questions and hold the first official course. Soon after, USPA conducted courses at Pepperell Skydiving Center in Massachusetts and West Point Skydiving Adventures in Virginia.

The USPA Board soon rescinded the motion to require all drop zones to use the ISP as a mandatory student training program, since many DZs complained that they had developed and preferred their own courses. However, eventually almost all drop zones either adopted it as written or incorporated different parts of the program into their own student training programs. The payoff has been an influx of A-license holders who are much safer and better skydivers than those from the past, meaning that drop zones experience fewer injuries and accidents.

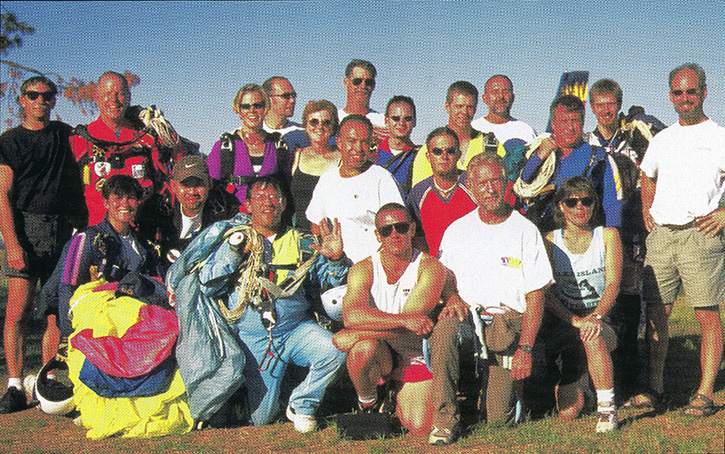

The first USPA Coach Rating Course attendees gather for a group photo.

Examiner Rating

In 1961, when static-line was the only method of student training, many of the most active instructors in the country began development of the Instructor Examiner rating, a rating to certify those who trained instructors. USPA held the first IE certification course in Phoenix, Arizona, in February 1962. That first class of instructor examiners was a veritable who’s who of 1960s skydiving. Lee Guilfoyle, Russ Gunby, Jacques-André Istel, Paul Poppenhager and Lew Sanborn were among that first class.

The USPA Instructor Examiner rating (now called simply “Examiner rating”) was originally developed to define the all-around skydiving expert on the drop zone. Not only did it require jumping experience and a USPA D License, it also included an extensive written test on a variety of skydiving and non-skydiving topics, knowledge of first aid and the acquisition of a parachute rigger certificate. Probably due to the rigorous demands, there were only 70-80 current and active examiners each year for the first four decades of the program.

In the early 2000s, when USPA made major changes to its entire instructional rating system with the introduction of the Integrated Student Program, these changes affected examiners. The sport of skydiving was now many times more complex than when the examiner rating first developed. There were four first-jump methods: static-line, instructor-assisted deployment, accelerated freefall and tandem, each with its own method-specific instructor rating and certification course, as well as a new USPA Coach rating.

There was a lot of discussion among the USPA Board members regarding the title for those who would run USPA Coach and Instructor Certification Courses. At the time, “instructor examiners” ran static-line instructor rating courses and “course directors” ran coach, AFF and tandem rating courses. It was a hodgepodge of terminology, rules and requirements. All the rating courses were badly in need of standardization.

At the same time, the board merged the jumpmaster rating (those who could instruct students but not teach the first-jump course) into the instructor rating (those who could both instruct and teach the first-jump course) for all training disciplines. The goal was to simplify the rating hierarchy to three levels: USPA Coach, Instructor and Instructor Examiner. With a slight change to the Basic Safety Requirements, the board ensured that former jumpmasters could easily meet the instructor requirement when renewing their ratings by either teaching the full first-jump course or performing a complete first-jump course review training with a student.

Beginning in the mid-2000s, the Coach Examiner and Static-Line, IAD, AFF and Tandem Instructor Examiner Rating Courses began focusing almost entirely on teaching and evaluating new coach and instructor rating candidates. (At the summer 2020 board meeting, the board simplified the term “instructor examiner” to just “examiner,” but left the courses themselves unchanged.) The rating-system overhaul and restructuring was an arduous task that took years to accomplish, and existing examiners needed to meet the new requirements before teaching rating courses. However, it ushered in enormous improvements to the quality of instruction at all levels and has made the sport of skydiving safer than ever.

The advances in USPA’s student and instructor-training programs over the last six decades has been nothing short of phenomenal. The reduction in accidents and the improvement in the skills and knowledge of newly licensed skydivers proves that the changes are moving the sport in the right direction. It has literally taken decades to move forward and improve each rating program. But the only true constant is change. The Safety and Training Committee will continue to evaluate and change all the rating programs as necessary. And even though it is often met with resistance, change is almost always a good thing. Who knows what tomorrow will bring?

About the Author

About the Author

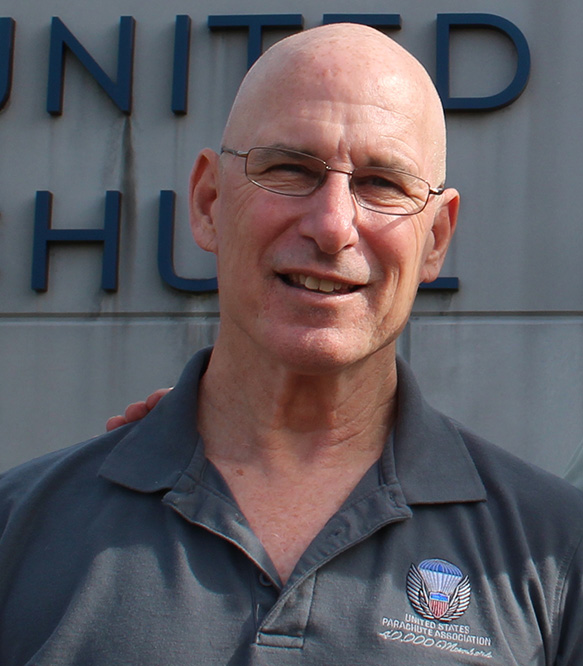

Jim Crouch was USPA Director of Safety and Training from 2000-2018. He spent months researching through old board minutes, Parachutist magazines and the book “Tandem—The Beginnings of an Industry That Made Human Flight Accessible to the Average Person” by Jen Sharp. He also interviewed many of those who were involved, including T.K. Donle, Jack Gregory, Mike Johnston, Rob Laidlaw, Mike Marcon, Mike Marthaller, Bill Morrissey and Paul Sitter and used his own personal experiences of the many changes that took place during his time at USPA.